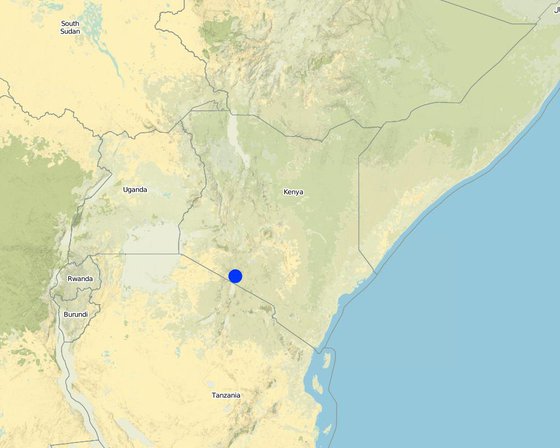

This technology is applied in the South Rift Valley, Kenya, across a semi-arid landscape, with erratic rainfall averaging 400-600 mm per annum. Water availability is an issue. The perennial Ewaso Ngiro South river flows through the Shompole swamp, a vital drought refuge for livestock and wildlife, before ending up in Lake Natron. The area, roughly 1000 km2, is covered by two group ranches, Olkiramatian and Shompole, which are managed as a single ecological unit. A group ranch is a jointly owned freehold land title given to the customary occupants of communal lands. The total number of occupants of both ranches number roughly 20,000 people, with the majority belonging to the Maasai ethnic group. The ranches have not been subdivided and are not fully sedentary, unlike many other areas of southern Kenya.

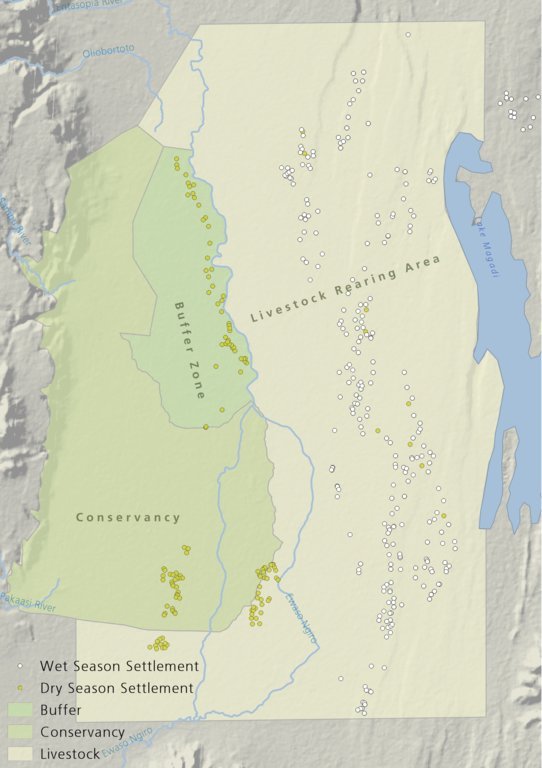

There is a long history of co-existence of wildlife and livestock in Maasialand. In Olkiramatian and Shompole seasonal livestock movements and herding practices are formalized by group ranch grazing plans governed by local committees. The wet season grazing areas are termed “livestock rearing zones”. The dry season grazing areas have been retained as “grass banks” for livestock, and since the early 2000s, have been used additionally as wildlife conservancies for ecotourism (see figure below). Livestock rearing occurs to the east of the Ewaso Ngiro river; grass banks and the wildlife conservancy to the west. Grazing committees from both group ranches manage livestock access to certain areas, with the conservancy (grass bank) rested during the wet season of up to six months. When grazing is permitted in the conservancy, as the dry season progresses, temporary settlements are limited to an area called the “buffer zone”. Livestock must then move into the conservancy from the buffer zones to access this late season grazing. The “livestock rearing zone” is permanently settled and grazed year-round. Within each zone there are small “Olopololis” (grass banks of a few hectares), situated near individual settlements and used to maintain higher quality pasture for weak and young animals. This management strategy ensures that the dry season grazing area is rested during the rains, and it helps to maintain consistently higher biomass and taller grass than that of the wet season grazing area. The higher biomass also corresponds to a rainfall gradient running from the Nguruman Escarpment edge in the western extremity of the group ranches to the dry central rift valley floor in the east. The biomass in the dry season area is used by both livestock and wildlife grazers during the late dry season and in droughts. The grass bank is only grazed out during prolonged dry periods. The Maasai employ a strategy of using the shorter milk-producing grasses of the livestock areas during the rains and the coarser grasses in the grass banks for the dry seasons. The shorter wet season pastures have a higher nutrient content and greater digestibility than the grass bank: this is very important for lactating females. The grass is kept short from both grazing by livestock during the growing seasons and due to intrinsic differences caused by shallower soils and lower rainfall in these grazing areas.

Within this broader governance framework and control of grazing areas, individual decision making is also permitted within these controlled areas. This allows herders to manage livestock to improve production in relation to each herd. For example, individuals might split the herd to take advantage of different energy and nutrient requirements of lactating females, bulls, and calves.

This maintenance and exploitation of forage heterogeneity is vital to the productivity and resilience of the landscape, and this heterogeneity exists at multiple scales, with the major differences existing between the grazing areas, but also smaller difference within them. Resource heterogeneity facilitates wildlife-livestock coexistence. This heterogeneity creates a matrix of varying quality and quantity of forage. Wildlife species have different metabolic requirements and diets, and this varied base ensures that a diverse wild ungulate population is maintained year-round. Late season forage boosts the resilience of wildlife during extreme events. This technology requires a governance structure that is both responsive to the changing ecological conditions and able to build consensus and enforce grazing management.

Lieu: Olkiramatian, Kajiado, Kenya

Nbr de sites de la Technologie analysés: site unique

Diffusion de la Technologie: répartie uniformément sur une zone (approx. 100-1 000 km2)

Dans des zones protégées en permanence ?:

Date de mise en oeuvre: 2004

Type d'introduction

This is in contrast to areas without seasonal grazing management.

This management system works best to preserve lower quality higher biomass fodder. Quality may not increase dramatically, but the creation of short areas of well-fertilized grass near settlements may increase the local quality of fodder during the wet season.

In comparison to other systems the preservation of late season grazing is crucial in preventing complete losses of livestock during droughts.

Management of land in this manner relies on traditional ecological knowledge for both individual and community decision making. This is dependent on cultural values and understanding, and underpins grazing management in Maasai society.

This method increase vegetation cover by maintaining heterogeneity of forage resources across the landscape, and resting pasture seasonally to allow for vegetation regrowth.

Late season forage available. Recovery and rest allows for greater productivity and rainfall use efficiency.

Maintenance of spatial and temporal heterogeneity of forage resources ensures that wildlife species have access to the variable resources that they require over time.