The Kalpavalli conservation approach is renowned for its focus on restoring common lands through the efforts of a cooperative society based on a federation of village forest committees. Community members are the beneficiaries. Through this approach, 6,500-acres (2,630 hectare) of arid and severely degraded common lands, have been successfully rejuvenated over the past 33 years. An NGO, Timbaktu Collective, has facilitated the conceptualisation and implementation of the approach.

The primary stakeholders are marginalized community members, including Dalits (the socially disadvantaged lowest castes), who have traditionally been landless labourers and pastoralists. Timbaktu Collective has played a critical role in community mobilization, capacity-building, training, and documentation. The approach empowered the lower castes to participate actively in the decision-making process and enabled them to advocate for benefits from government programmes. However, the lack of absolute ownership of the common lands and the potential influence of private parties with vested interests remain challenges.

The programme offers social and technical support. Details of the approach and its key focusses are as follows:

1. Social

Livelihoods: The Kalpavalli area is officially designated by the government as "wastelands", a contentious term which is applied to lands which the government does not consider economically productive. These lands are technically administrated by the State Government, but in most cases are either ignored or given to companies to establish factories or industrial estates. However, the Kalpavalli conservation approach ensures that traditional grazing and usage rights by communities are recognised. This facilitates sustainable land use centred on grazing, harvesting of non-timber forest produce, and more. The approach further promotes community management of common resources, joint responsibility for land protection, access to income generation from minor forest produce – all based on sustainable resource management.

Ownership and rights to resources: Grazing lands are largely under the technical ownership of the government, where traditional usage rights are permitted but not awarded legal status. The main challenge here is uncertainty about long-term ownership and rights to access. The approach therefore aims to secure usage, control, and ownership rights for the local community users. This is enabled through the creation of a community cooperative. The NGO and the cooperative have together been exploring various legal options to secure community ownership of the land.

Participation: The approach relies on social and technical methods, emphasizing community engagement. Social techniques include street theatre, community outings, participatory discussions, and voluntary service (“Shramadhanam”) to educate and mobilize the largely illiterate population.

Membership and monitoring: Members contribute an annual fee to access grazing and fuelwood collection. The approach includes policies for both protecting and monitoring common resources.

Organization development: Capacity-building, conflict resolution and organization management are facilitated through training and workshops.

Enterprise development: The community cooperative has launched eco-tourism initiatives to generate income, reinvesting profits into conservation efforts.

2. Technical

Restoration: The initial focus was on land protection, as common lands were degraded. In the initial years a key focus was on planting but then restoration work was modified as the land responded. Efforts have included protection from logging, creating firebreak lines, seed collection of native species, stream clearing, rotational grazing management, constructing rock-filled dams - and other watershed development work.

Protection of the commons: Stones were used to demarcate the land, and volunteer groups ("Vana Samrakshana Samithi") were established to prevent overgrazing and protect the area from uncontrolled fires.

Earthworks: Soil and water conservation measures such as rock-filled dams and earth bunds were introduced to reduce soil erosion and enhance groundwater recharge.

Research and management plans: Researchers helped map and share understanding of biodiversity. Biodiversity conservation, including both flora and fauna became a focus, with savannah ecology management plans developed.

Trees and vegetation: Initial attempts at using nurseries for propagation met with little success - and were replaced by seed broadcasting and propagation of local wild species. Seed huts were built to store seeds gather from this indigenous vegetation.

Местоположение: Anatapuram District, Andhra Pradesh, Индия

Дата ввода в действие: 1992

Дата завершения: н/п

Тип Подхода

| Какие заинтересованные стороны/ организации-исполнители участвовали в реализации Подхода? | Перечислите заинтересованные стороны | Опишите роли заинтересованных сторон |

| местные землепользователи/ местные сообщества | 10 local village groups all from marginalised lower castes. | Watch and ward, land management and participatory processes. |

| организации местных сообществ | The Kalpavalli Tree Growers Cooperative (registered name) comprising over 250 members. Also referred to as the 'Cooperative or community Cooperative' in various places in this document. | Mobilisation, management and participatory processes. |

| эксперты по УЗП/ сельскому хозяйству | Researchers, academics and university groups. | SLM technologies, trainings, data collection. |

| ученые-исследователи | inhouse and external ecologists and social scientists | documentation and SLM |

| общественные организации | The timbaktu collective | ideation, catalyst, implementation, technical, administrative, financial and logistical support. |

| местные власти | Local Panchyath, District Collector, Block Education officer | legal owners of land, facilitate education and help with conflict management. |

| международные организации | Interntional donor agencies | funding, monitoring and evaluation. |

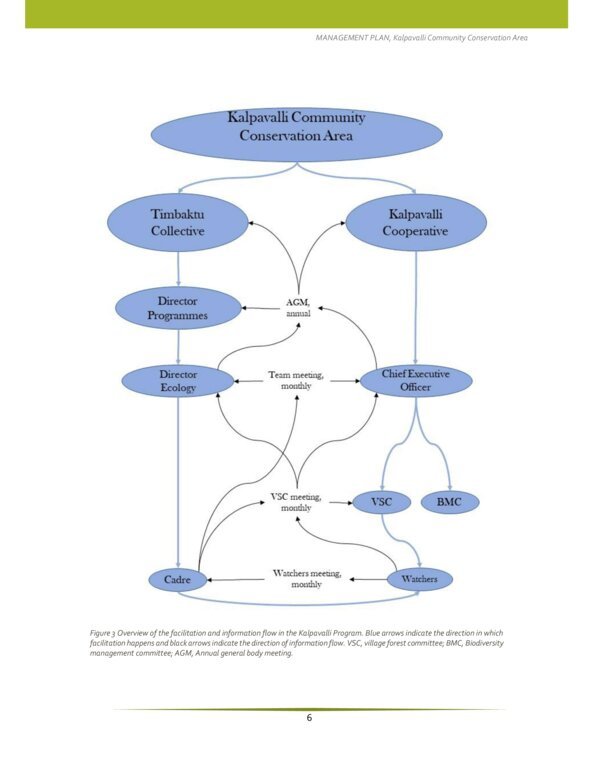

Overview of the facilitation and information flow in the Kalpavalli Programme, excerpt from the Kalpavalli Management Plan

Решения принимались

Принятие решений было основано на

Seed preservation and collection, grassland and rangeland management and ecology, wildlife conservation, bird watching, aquatic ecology, human-wildlife conflict, GIS basics, ecotourism, gender training, evolutionary biology.

From the year 2008, several formal research projects were taken up in the Kalpavalli area. One of the first was to do a physical walk along with marked locations along the BURUJULU (boundary markings) in order to make a GPS map. Post that, in 2013 there was a Biodiversity assessment done for both flora and fauna. Soon after a Wolf and Vulture questionnaire was carried out among land users and other community members to understand villager’s mindsets towards these two threatened species. The findings, along with other smaller questionnaires were compiled into another research study and report that outlined a Management Plan for the Kalpavalli Cooperative. Fauna specific research with camera trapping and field notes allowed Researchers to establish Kalpavalli as a critical habitat and corridor, especially for the vulnerable Indian Grey Wolf.

Most of the research over the years was carried out by Independent Ecologists and Wildlife Biologists. Mr. Siddharth Rao, Naren Sreenivasan, Gautham Gollapalli and Joseph Vattakaaven are among the researchers who have done extensive work on the Kalpavalli approach.

NREGA and Food For Work Programmes

Трудозатраты, вложенные землепользователями были

The NREGA Act and The Food for work Government programme

Prior to the approach, these specific communities and castes were not involved in discussions or decisions based in and around their villages. Over the years, the land users feel all decisions regarding their common resources such as fodder, thatch grass, streams and waterways were all made in a participatory fashion, and led by the lower caste members.

Yes. This was because of seeing the effects of various technologies taking shape on the landscape and then slowly increasing the area of the Commons that were added to be protected and nurtured. Photo documentation helped monitor and share results to make it easier to implement more evidence based decision making possible, especially for the illiterate community members. Researchers documenting and collecting data has helped this process.

Yes. Having the support of the NGO team members to help oversee and propagate technologies allowed for more village groups to get involved in healing the lands closest to their area. This had various impacts such as mobilizing the community as well maintaining all records for any incentive-based work to be immediately reimbursed. This built trust as well to maintain the SLM technologies once implemented.

Definitely. Having a strategic approach to the technologies meant that existing social norms and cultures were used in a participatory way. Examples are shramadaanam (voluntary work for a specific goal such as making making fire lines), desilting waterbodies in the dry season, putting out fires using existing techniques such as green palm fronds etc. If these methodologies were not used in a resourceful manner, all the technologies would have proved much more expensive to implement in field.

Prior to the approach, this land area was degraded and unmanaged for any returns, tangible and intangible. By starting the initial village groups, members put together small savings to carry out certain activities while the NGO also raised funds for the same. This process greatly helped to initiate and then continue to mobilize financial resources. Currently, the Eco tourism model also follows the same ideology of mobilizing funds for SLM in the area.

Yes definitely. Building on a few existing technologies, the SLMs introduced were simple, practical and enabled community members to easily join in the process.

Village members who are not part of these committees were also impacted by these activities as awareness grew about restoration practises and methods to aid the process.

Yes definitely. The Cooperative approach intrinsically is a people led structure that is open to sharing knowledge and involving others in processes. The community, NGO, Government as well as other stakeholders such as migratory pastoralists, research organizations, farmer cooperatives, Cooperative of People with disabilities and local Government school children are all stakeholders with whom collaboration has been initiated and strengthened.

Significantly. In the initial years conflicts arose between villages over shared resources such as fodder and thatch grass. These were resolved by interventions from the NGO members. In later years, conflicts with windmill owners, private quarry owners, political parties looking to grab land were all dealt with in a peaceful manner with dialogue and exerting land use rights at the fore.

Yes significantly. Kalpavalli works in 10 villages and in these villages with the most socially and economically marginalized communities. The Village members as well as traditional migratory pastoralists make regular income as well as livelihood supports thanks to this approach. The land users feel that this approach has had both immediate as well as long term benefits for socially and economically backward groups.

In the initial years, men were reluctant to have women join the discussions in the ‘male dominated’ areas of the village where meetings usually took place. Women too were hesitant to participate in these gatherings. However, they were encouraged to join in, especially as they were the ones doing rounds to collect firewood and fodder for the homestead. Slowly, they got involved and today play an important role in the leadership. However, daily patrol, watch and ward work is not undertaken by them due to safety concerns. School girls were encouraged to join day long SLM activities such as seed broadcasting and collection which was absolutely not common before. Some members pointed out that gender equality trainings by the NGO opened their eyes to shared leadership and responsibility of the commons.

Many members encourage their children to attend the camps and awareness workshops that the Ngo organize. The focus of these is on grassland biodiversity and ecosystems along with fun games, activities and cultural dances and songs that celebrate nature. These training camps has had several hundred children and youth attend and has fostered a strong connection with their wild and common lands

Land tenure was not impacted but user rights were strongly bolstered. Community members never undertook measures to heal the land while it was just listed as the Commons. Since this approach, the fact that the land was restored and proved to become a massive resource for the community definitely improved user rights. As for tenure, it still comes under the Government.

Community members interviewed for this case study pointed out two distinct ways in which the approach has led to food security. One is that the protection and management of the streams and the check-dams has ensured that the watershed works well every monsoon with sufficient water collection in the big lakes downstream. The water from here is used by the farming community to grow a variety of greens and vegetables that are then mostly sold locally in the village itself. The other factor they pointed out was that abundance of fodder for small ruminants has ensured that meat consumption, especially of free-range goat and sheep mutton has been possible thanks to this approach. In other villages, pooer sections of the community have no other protein source than to buy cheaper farmed ‘broiler chicken’ meat, which is weak in nutrition and pumped with a lot of steroids and antibiotics.

In this regards, the traditional market access for NTFP was strengthened. Livelihoods from seasonal broom grass collection, thatch grass, palm fronds for mats and basket weaving, wild berries and various flora for ethno- veterinary preparations have all been helped. The collection and sale of these have certainly increased the access to markets for these sections of the community, especially women from the lower castes. Additionally, market-based solutions such as an eco-tourism venture withing the conservation area is up and running. This provides revenue to the Coopertive from tourist who visit the restoration site. All this work in relation to markets has been led by the Timbaktu Collective.

Access to water yes. Sanitation not necessarily as that comes under the management of the Municipality of the local government bodies. The SLMs in the approach have had a massive impact on consistent water levels in the entire watershed as well as recharging the underground aquifers.

As a lot of the SLMs were taken from the Timbaktu handbook, solar powered spaces were a big take away. All infrastructure in the Kalpavalli area is solar powered