Restoration of game migration routes across the Namib Desert [Namibia]

- Creation:

- Update:

- Compiler: Ibo Zimmermann

- Editor: –

- Reviewers: Rima Mekdaschi Studer, Simone Verzandvoort

NamibRand Nature Reserve

approaches_3286 - Namibia

- Full summary as PDF

- Full summary as PDF for print

- Full summary in the browser

- Full summary (unformatted)

- Restoration of game migration routes across the Namib Desert: Nov. 2, 2021 (public)

- Restoration of game migration routes across the Namib Desert: Oct. 6, 2018 (inactive)

- Restoration of game migration routes across the Namib Desert : April 13, 2018 (inactive)

- Restoration of game migration routes across the Namib Desert : Feb. 23, 2018 (inactive)

- Restoration of game migrations across Namib Desert: Jan. 12, 2018 (inactive)

View sections

Expand all Collapse all1. General information

1.2 Contact details of resource persons and institutions involved in the assessment and documentation of the Approach

Name of project which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

NamibRand Nature ReserveName of the institution(s) which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

Namibia University of Science and Technology ( NUST) - Namibia1.3 Conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT

When were the data compiled (in the field)?

01/11/2017

The compiler and key resource person(s) accept the conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT:

Yes

2. Description of the SLM Approach

2.1 Short description of the Approach

Seventeen former sheep farms have been joined to form the world’s largest private nature reserve aimed at regenerating biodiversity to support high-quality low-impact tourism, environmental education and research. All farm owners are members of the management association.

2.2 Detailed description of the Approach

Detailed description of the Approach:

The NamibRand Nature Reserve is a not-for-profit organisation in south-western Namibia. It was founded in 1984 through the initiative of one farm owner, Albi Brueckner, who agreed, with 16 neighbouring farmers, to jointly manage their 215,000 ha for nature conservation and tourism. Its aims are:

To conserve biodiversity for the benefit of future generations and protect the sensitive and fragile environment.

To create a nature reserve with a healthy and functioning ecosystem, providing a sanctuary for flora and fauna, and to facilitate seasonal migratory routes in partnership with neighbours.

To promote sustainable utilisation – through ecologically sustainable and high-quality tourism and other projects.

To achieve a commercially viable operation to ensure continuity and financial independence.

The NamibRand Nature Reserve’s contributions to biodiversity conservation, in accordance with the environmental management plan, include the following:

• Removal of over 2,000 km of fencing to reinstate wildlife migration routes.

• Re-introduction of giraffe and cheetah.

• Bolstering numbers of red hartebeest and plains zebra.

• Removal of alien invasive vegetation such as Prosopis species and replacing these with indigenous Acacias.

• Zonation according to land use areas, including the setting aside 15% of the reserve as a wilderness area.

• Limiting overnight visitors to an average of one bed per 1,000 ha, and 25 beds per location.

• Conducting annual game counts, with results posted on the website www.namibrand.org

• Monitoring the endemic Hartmann’s mountain zebra through the use of camera traps. Results are at: http://www.nnf.org.na/project/mountain-zebra-project/13/1/12.html

• Continuous monitoring of drivers and determinants of environmental change to guide the management plan. Results are posted online at: http://www.landscapesnamibia.org/sossusvlei-namib/rainfall-monitoring

• Hosting researchers to study game migration routes. Results of wildlife monitoring, through the use of GPS collars are at: http://www.landscapesnamibia.org/sossusvlei-namib/research

• Hosting the Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust (NaDEET), to empower and educate schoolchildren for a sustainable future. It operates an environmental education and sustainable living centre (www.nadeet.org).

• A lighting management plan to qualify as an international dark sky reserve that avoids negative consequences of light pollution on biodiversity – which can interfere with animal navigation, reduce the hunting success of predators and prevent moths from pollinating (http://www.darksky.org/idsp/reserves/namibrand)

• A water management plan, including monitoring of the impact of a water hole on the surrounding vegetation.

• Implementation of tourism and land use zonation plans.

• Capture and sale of live game for wildlife population management purposes.

• Plans to develop a horticultural project to grow indigenous medicinal plants for commercial production, creating local jobs and income for conservation.

Rangeland management is achieved largely through continual monitoring and control of animal populations, and the balance between functional groups of their species, and turning off the water supply where grasses are in need of rest. Local outreach efforts focus mainly on predator-livestock management on neighbouring farms.

Stakeholders comprise the land owners, who agree on joint management, and the tourism concessionaires who operate in the reserve under contract. The reserve employs 12 people who are responsible for day-to-day management and maintenance. Biodiversity and land management are funded from park fees collected by the concessionaires from tourists who stay at their establishments. This small management team is possible, because tourism concessionaires offer scenic game drives across the reserve, while on the lookout for required action. For example, guides report issues such as leaking water pipes, unusual wildlife sightings, injured animals, and trespassers (etc.) to reserve managers, who can then react.

Land owners who have connected their land to the reserve and are members of the NamibRand Nature Reserve Association have the option of serving as directors of the association, with joint decision making powers. Those who choose not can still contribute to the strategic mission of the reserve at annual general meetings.

2.3 Photos of the Approach

2.4 Videos of the Approach

Comments, short description:

Short introduction to the reserve

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QVQgJlBXn78

Date:

01/04/2015

Location:

NamibRand Nature Reserve

Name of videographer:

IUCN-PAPACO

Comments, short description:

View of landscapes in the reserve

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8LZI2ZtPhbg

Date:

15/09/2014

Location:

NamibRand Nature Reserve

Name of videographer:

Christine Guillot, Etendues Sauvages

Comments, short description:

Organic garden at lodge in the reserve

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7RVKfeQ-0M

Date:

05/04/2016

Location:

NamibRand nature Reserve

Name of videographer:

Ticket2Utopia – Dr. Paul Goddard

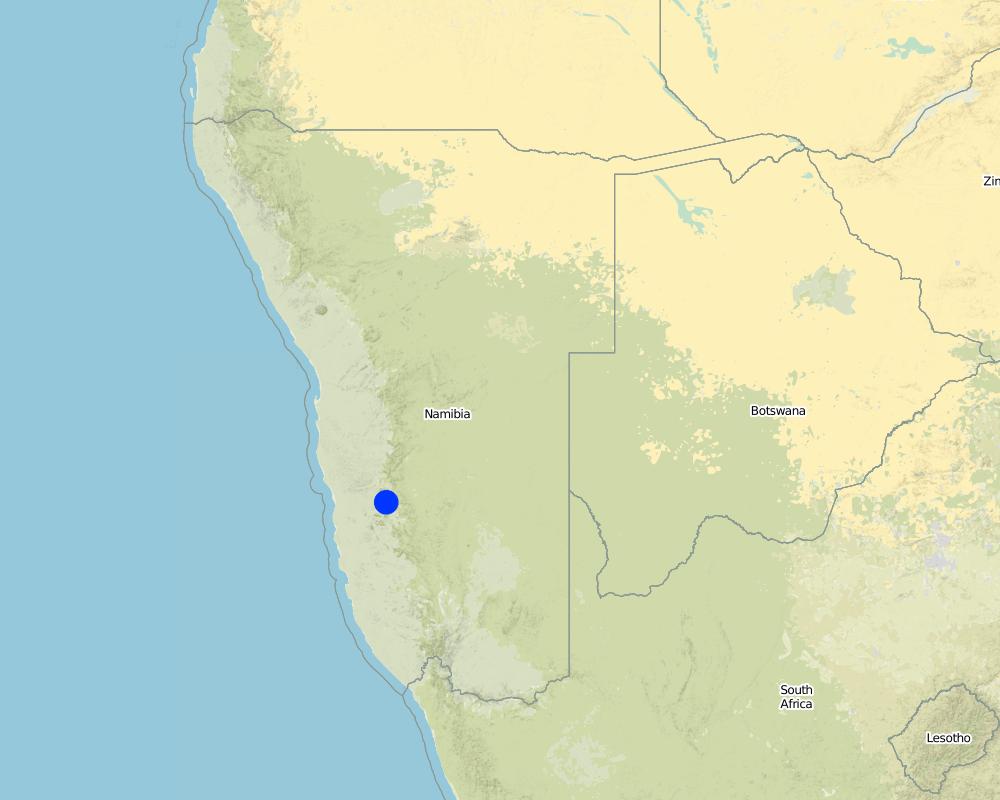

2.5 Country/ region/ locations where the Approach has been applied

Country:

Namibia

Region/ State/ Province:

Southwestern Namibia in the Namib Desert.

Map

×2.6 Dates of initiation and termination of the Approach

Indicate year of initiation:

1984

If precise year is not known, indicate approximate date when the Approach was initiated:

10-50 years ago

Comments:

The first property was purchased in 1984. The reserve was registered as a Game Reserve in 1992 and registered as the NamibRand Nature Reserve, an Association Not for Gain, in 2002

2.7 Type of Approach

- recent local initiative/ innovative

2.8 Main aims/ objectives of the Approach

The approach aims, through participatory land use planning, to restore ecosystem function in the reserve and its surroundings to support high-quality, low-impact tourism that provides the means to support environmental education and other conservation projects.

The overall Strategic Vision of the NamibRand Nature Reserve is to manage the Pro-Namib area, alongside the Namib Desert, for the enhanced conservation of the landscape and its biodiversity.

2.9 Conditions enabling or hindering implementation of the Technology/ Technologies applied under the Approach

social/ cultural/ religious norms and values

- enabling

The area was historically visited by migrant San people and more recently by Nama people, who have settled permanently elsewhere. Since no people were living permanently in this hyper-arid ecosystem, the use of the area exclusively for nature conservation remains uncontested.

availability/ access to financial resources and services

- enabling

The establishment of the reserve was initially possible through the ample financial resources of wealthy, altruistic and philanthropic investors.

- hindering

The properties that make up the NamibRand Nature Reserve are located in a hyper-arid ecosystem. Farmers who attempted livestock farming there in the past almost all failed to establish economically viable farms, and most of them overextended themselves financially, resulting in the foreclosure of their farms. For this reason, the area became known as the “Bankruptcy Belt”. Banks were, in the past, extremely reluctant to extend loans to landowners in this area, due to the low value and low agricultural potential. In recent years, the successes of conservation and tourism have changed this situation and banks are now prepared to accept farms with such land use as collateral for extending loans.

institutional setting

- enabling

Progressive government company laws, such as the possibilit y to register a Section 21 company (“Association Not for Gain”) allow financial resources to be re-invested in conservation so as to further the objectives of the non-profit association. Section 21 companies also do not have to pay company taxes to the government.

collaboration/ coordination of actors

- enabling

Articles of Association and the management plan allow for the creation of a management team that effectively coordinates all activities on the reserve.

legal framework (land tenure, land and water use rights)

- enabling

Rights and therefore the possibility to benefit from wildlife are enshrined in the Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1975.

- hindering

The current Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1975 does not allow for the registration of private nature reserves. The status of the land with the government thus remains as agricultural land, and law enforcement has to rely on common law such as trespassing on private property.

policies

- enabling

Progressive, enabling policies of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, such as the tourism policy and the parks and neighbours policy ensure meaningful collaborations between the public and the private sector. See http://www.met.gov.na

land governance (decision-making, implementation and enforcement)

- enabling

Good governance is achieved through the adoption of Articles of Association and management plans. These guide decision-making and enable implementation. A set of rules, called the Vade Mecum, enable enforcement.

knowledge about SLM, access to technical support

- enabling

Good networking, membership to various professional bodies and collaboration with universities and researchers ensure good knowledge about sustainable land management and technical support.

markets (to purchase inputs, sell products) and prices

- enabling

A well-established tourism market to Namibia ensures a steady stream of visitors to the NamibRand Nature Reserve, enabling the collection of park fees and thus ensuring income for the reserve.

- hindering

The remoteness of the reserve, 150km from the nearest town, results in expensive transport charges for goods and inflated prices for professional services.

workload, availability of manpower

- enabling

Guides from tourism concessions on the reserve allow for sharing of workloads. Availability of human resources in the region is ample.

3. Participation and roles of stakeholders involved

3.1 Stakeholders involved in the Approach and their roles

- local land users/ local communities

17 former livestock farms owned by 12 companies, now converted to tourism enterprises

Some of them serve as directors of the NamibRand Nature Reserve Association, for joint decision making

- SLM specialists/ agricultural advisers

12 reserve management staff

To manage the reserve

- researchers

Visiting researchers from various academic institutions

To conduct research to help with applied research for management and "interest research" such as on “fairy circles”, which can be seen in the cover photo. The origin of these circles of bare soil surrounded by grass is still being disputed among scientists (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2VNyo9AoA8I). There is a Wildlife monitoring programme partnership with Namibia University of Science and Technology and the Greater Sossusvlei Landscape Association

- teachers/ school children/ students

4 full-time teachers at NADEET and 10 instructors at hospitality training centre.

To expose about 1000 visiting students per year to environmental education and to provide vocational training to about 100 trainees per year.

- NGO

Cheetah Conservation Fund and Giraffe Conservation Fund.

To reintroduce predators and wild herbivore species.

- private sector

Neighbouring farms

Co-management of the larger landscape with like-minded neighbours, as indicated at: http://www.landscapesnamibia.org/sossusvlei-namib/

- national government (planners, decision-makers)

Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

To assist with law enforcement and wildlife monitoring.

- international organization

Member of IUCN

For advocacy and knowledge sharing.

3.2 Involvement of local land users/ local communities in the different phases of the Approach

| Involvement of local land users/ local communities | Specify who was involved and describe activities | |

|---|---|---|

| initiation/ motivation | self-mobilization | The founding farm owner approached philanthropic donors to buy neighbouring farms and invest in tourism facilities and environmental education centre. |

| planning | external support | In 1991, external experts provided advice for planning of the reserve. Influential persons involved included Chris Brown, Hugh Berry and Haino Rumpf of the Ministry of Environment, and Mary Seely of the Desert Research Foundation. |

| implementation | self-mobilization | Management staff were appointed in 1991, and paid for from the conservation levy raised from use of tourism facilities in the reserve. |

| monitoring/ evaluation | self-mobilization | Reserve management staff do the monitoring, paid for by the conservation levy. |

| research | external support | Research institutions conduct research after paying a small service fee. |

3.4 Decision-making on the selection of SLM Technology/ Technologies

Specify who decided on the selection of the Technology/ Technologies to be implemented:

- mainly land users, supported by SLM specialists

Explain:

The Reserve's vision and mission were set up by its directors, who comprise farm owners willing to serve in this decision making role, at the Initiation workshop in 1991. Management actions were then Implemented under the guidance of various specialists.

Specify on what basis decisions were made:

- evaluation of well-documented SLM knowledge (evidence-based decision-making)

- research findings

- personal experience and opinions (undocumented)

4. Technical support, capacity building, and knowledge management

4.1 Capacity building/ training

Was training provided to land users/ other stakeholders?

Yes

Specify who was trained:

- land users

- field staff/ advisers

- Tourism concessionaires

Form of training:

- on-the-job

- demonstration areas

- public meetings

Form of training:

- Exchange visits

Subjects covered:

Biodiversity conservation, financial management, tourism best practices, principles of co-management, human-wildlife conflict resolution, rehabilitation.

4.2 Advisory service

Do land users have access to an advisory service?

Yes

Specify whether advisory service is provided:

- on land users' fields

- at permanent centres

Describe/ comments:

Advice is provided by the Namibia Chamber of Environment, the Namibia Nature Foundation, the Ministry of Environment and Tourism Resource Centre, the Namibia University of Science and Technology, the Giraffe Conservation Fund and other wildlife biologists on issues such as determination of wildlife carrying capacities.

4.3 Institution strengthening (organizational development)

Have institutions been established or strengthened through the Approach?

- yes, greatly

Specify the level(s) at which institutions have been strengthened or established:

- local

Describe institution, roles and responsibilities, members, etc.

NamibRand Nature Reserve Association. All land owners are members, who elect the directors. They manage the reserve according to an agreed strategy.

Specify type of support:

- financial

Give further details:

Hiring of lawyers and auditors/accountants to establish the association.

4.4 Monitoring and evaluation

Is monitoring and evaluation part of the Approach?

Yes

Comments:

Impacts are monitored to feed back into management.

If yes, is this documentation intended to be used for monitoring and evaluation?

No

4.5 Research

Was research part of the Approach?

Yes

Specify topics:

- ecology

Give further details and indicate who did the research:

Determination of wildlife carrying capacities by wildlife biologists.

5. Financing and external material support

5.1 Annual budget for the SLM component of the Approach

If precise annual budget is not known, indicate range:

- 100,000-1,000,000

Comments (e.g. main sources of funding/ major donors):

Self funded from conservation levy collected from tourism income.

5.2 Financial/ material support provided to land users

Did land users receive financial/ material support for implementing the Technology/ Technologies?

No

5.4 Credit

Was credit provided under the Approach for SLM activities?

No

5.5 Other incentives or instruments

Were other incentives or instruments used to promote implementation of SLM Technologies?

No

6. Impact analysis and concluding statements

6.1 Impacts of the Approach

Did the Approach empower local land users, improve stakeholder participation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Interest in owning land has greatly increased. Land prices have risen and more tourism establishments were built.

Did the Approach enable evidence-based decision-making?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through monitoring, to determine wildlife carrying capacity.

Did the Approach help land users to implement and maintain SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Research and expert advice drives appropriate management for the ecology. There are no more sheep and associated weeds, while wildlife numbers increased.

Did the Approach improve coordination and cost-effective implementation of SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

By applying economies of scale. Managed holistically by a small, effective team.

Did the Approach mobilize/ improve access to financial resources for SLM implementation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through awarding of tourism concessions and collection of park fees.

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of land users to implement SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through various training and research activities.

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of other stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through accessing information and gaining knowledge from research.

Did the Approach build/ strengthen institutions, collaboration between stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through establishment of the association, appointment of the management team and information sharing.

Did the Approach mitigate conflicts?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through implantation of a joint management plan and shared vision.

Did the Approach empower socially and economically disadvantaged groups?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

There are no local communities living within the area, but children from all over the country visit the environmental education centre.

Did the Approach improve gender equality and empower women and girls?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through policies prohibiting gender discrimination, implemented by tourism enterprises.

Did the Approach encourage young people/ the next generation of land users to engage in SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through the environmental education and vocational training centres.

Did the Approach improve issues of land tenure/ user rights that hindered implementation of SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through establishment of the Association for joint management and guidelines that are followed in the management plan.

Did the Approach lead to improved food security/ improved nutrition?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through the organic garden of 1 ha irrigated with borehole water and featuring in one of the Youtube videos, the improved financial status of the area and access to meat of culled animals for reserve workers and tourists.

Did the Approach improve access to markets?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Due to serving tourism needs.

Did the Approach lead to improved access to water and sanitation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Workers have access to borehole water pumped for tourism.

Did the Approach lead to more sustainable use/ sources of energy?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Solar power is used to generate electricity and heat water.

Did the Approach improve the capacity of the land users to adapt to climate changes/ extremes and mitigate climate related disasters?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Based on naturally adapted species that are able to migrate.

Did the Approach lead to employment, income opportunities?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The current land use based on tourism supports times more employees per unit area compared with former sheep farming.

National economy:

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Contribution to national income through higher wages in the tourism industry.

6.2 Main motivation of land users to implement SLM

- increased profit(ability), improved cost-benefit-ratio

Through tourism, compared with former sheep farming.

- reduced land degradation

Reliance on more appropriate land use.

- reduced risk of disasters

Nature takes better care of itself and is more resilient to drought than sheep farming was.

- reduced workload

Sheep herders are no longer needed and there is a small, efficient management team, assisted by information provided through tour guides when their attention is required.

- prestige, social pressure/ social cohesion

Through membership of the association.

- environmental consciousness

Forms the vision of the association.

- enhanced SLM knowledge and skills

Improved resource management due to expert knowledge.

- aesthetic improvement

There are rules to prevent unsightly buildings and maintain the clear night sky, free from light pollution.

- conflict mitigation

Through the association constitution and discussions at planning meetings working towards the common goal

- Philantropic

Wanting to do good and contribute to conservation.

6.3 Sustainability of Approach activities

Can the land users sustain what has been implemented through the Approach (without external support)?

- yes

If yes, describe how:

Through income largely derived from tourism and partly from sale of captured game animals in accordance with the environmental management plan.

6.4 Strengths/ advantages of the Approach

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the land user’s view |

|---|

| The reserve is centrally and holistically managed by a team. |

| Resilience attained by the large unfenced ecosystem. |

| Land users coming together to sign and form a legally recognised body that is more robust. |

| Tourism is more profitable and sustainable than agriculture for such a hyper arid region. |

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view |

|---|

| Resilience to climate change through natural resources, using the competitive advantage of nature. |

| Private property excludes communal demands and allows fast and easy decision making on land use. |

6.5 Weaknesses/ disadvantages of the Approach and ways of overcoming them

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the land user’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

| There is currently no legislative support from government for protection of private land. | The new wildlife bill being drafted makes provision for privately protected areas. |

| In the eyes of the Ministry of Lands, there are only two types of land, either urban and gazetted (e.g. parks) or agricultural (subject to land tax). | Include a third category of land for protected areas, such as the desert margin being non-agricultural. |

7. References and links

7.1 Methods/ sources of information

- interviews with land users

Chief Executive Officer of the NamibRand Nature Reserve

7.2 References to available publications

Title, author, year, ISBN:

A Guidebook to the NamibRand Nature Reserve, 2017, ISBN 978-99945-85-14-4

Available from where? Costs?

Local bookshops for approximately USD25

7.3 Links to relevant information which is available online

Title/ description:

Website of NamibRand Nature Reserve

URL:

www.namibrand.org

Title/ description:

Website of Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust

URL:

www.nadeet.org

Links and modules

Expand all Collapse allLinks

No links

Modules

No modules