Participatory Grassland and Rangeland Assessment (PRAGA) [Georgia]

- Creation:

- Update:

- Compiler: Nicholas Euan Sharpe

- Editor: –

- Reviewers: William Critchley, Rima Mekdaschi Studer

საძოვრებისა და მდელოების თანამონაწილეობითი შეფასება

approaches_7570 - Georgia

View sections

Expand all Collapse all1. General information

1.2 Contact details of resource persons and institutions involved in the assessment and documentation of the Approach

Key resource person(s)

Project partners, land users, stakeholders of GCP/GEO/006/GFF, Regional Environmental Centre for the Caucasus (REC Caucasus) as article developer:

Name of project which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality Targets of Georgia through Restoration and Sustainable Management of Degraded Pasturelands (GCP/GEO/006/GFF)Name of the institution(s) which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

Regional Environmental Centre for the Caucasus (REC Caucasus) - Georgia1.3 Conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT

When were the data compiled (in the field)?

2019/2024

The compiler and key resource person(s) accept the conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT:

Yes

1.4 Reference(s) to Questionnaire(s) on SLM Technologies

Controlled Grazing [Georgia]

“Controlled Grazing” seeks to harness the behaviours and habits of ruminant livestock to enhance three key ecological functions, namely the removal of plant biomass (grazing), soil and vegetation disturbance (animal impact) and increased nutrient cycling (dung and urine), with the goal of increasing perennial grass establishment, pasture palatability and reducing …

- Compiler: Nicholas Euan Sharpe

2. Description of the SLM Approach

2.1 Short description of the Approach

The Participatory Rangelands and Grasslands Assessment Methodology (PRAGA) is a rapid, cost-effective framework for the integrated assessment of rangeland ecosystems, incorporating diverse data sources and participatory approaches. PRAGA facilitates stakeholder engagement through consultations and workshops, underpinned by community-based mapping of grazing areas, land use dynamics, and trend analyses.

2.2 Detailed description of the Approach

Detailed description of the Approach:

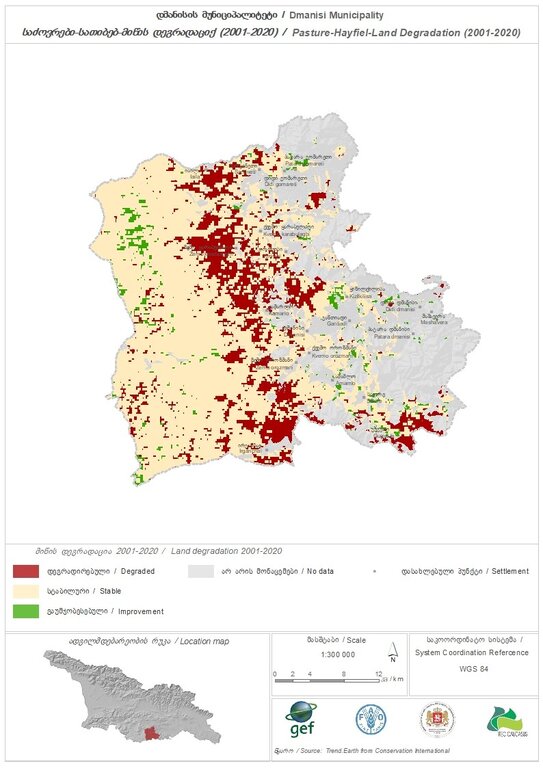

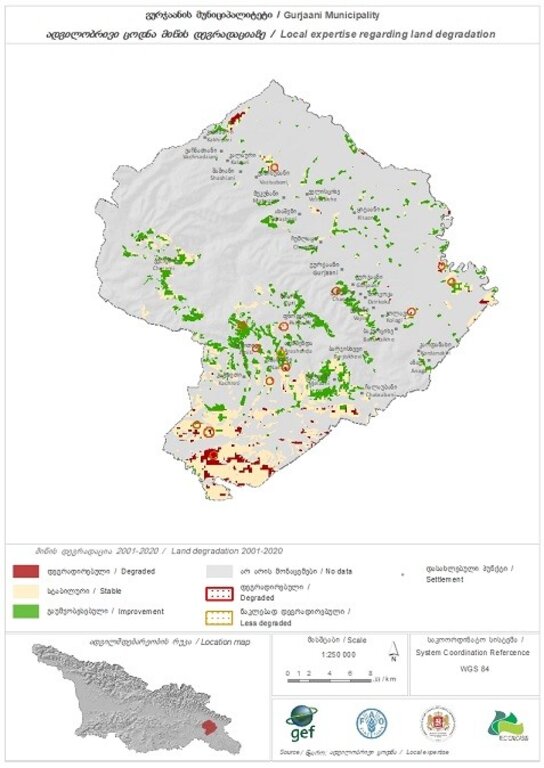

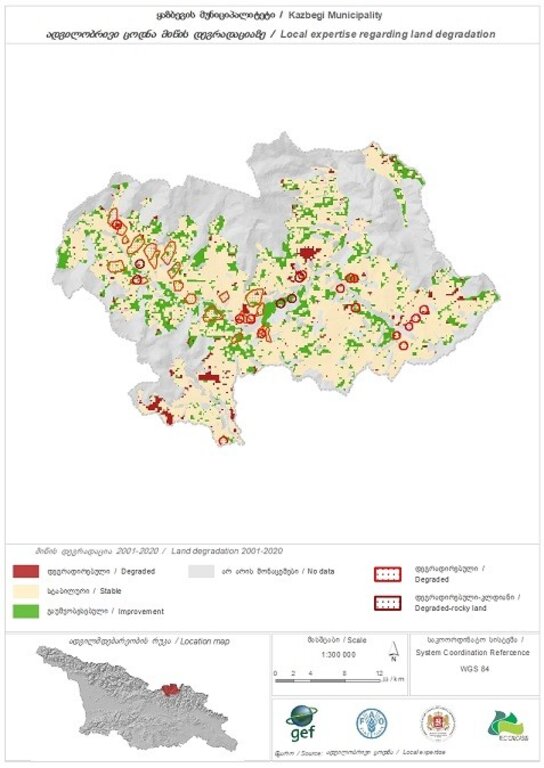

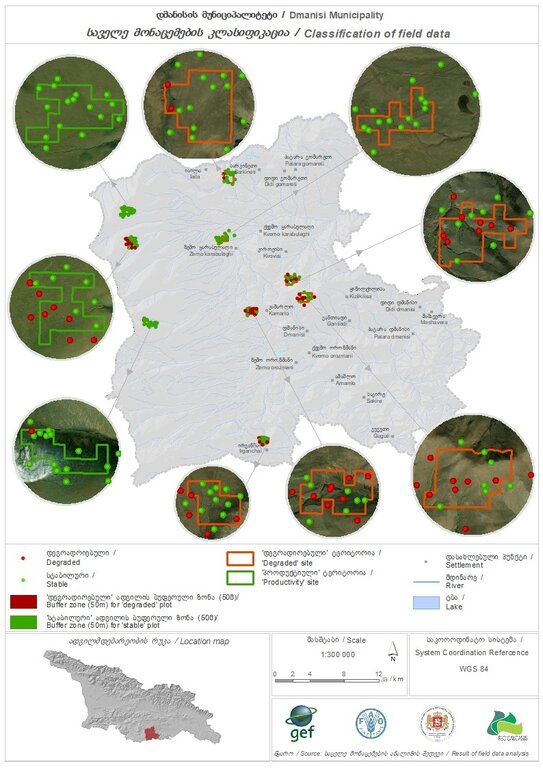

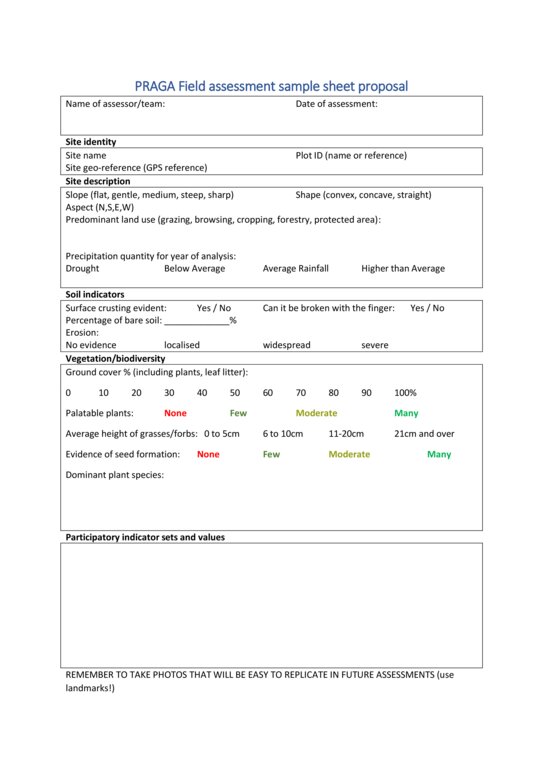

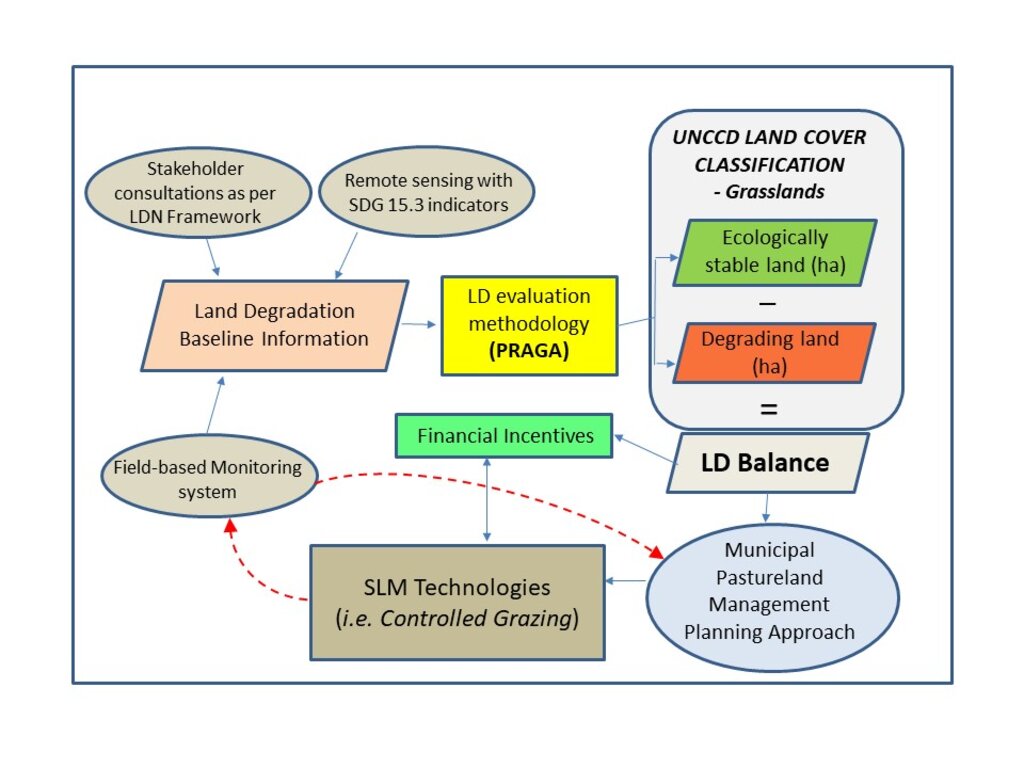

The PRAGA methodology is structured around three primary sources of information: (a) stakeholder inputs from Focus Group Discussions, Key Informant Interviews, and participatory mapping exercises; (b) field-based ecological and land-use surveys; and (c) remote sensing data (see: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1731318/). These are complemented by national topographic and thematic maps, cadastral records and land tenure documentation. In this project, the assessment outputs were integrated into an interactive, web-based platform, enabling users to visualize, manipulate, and analyse datasets related to land degradation (LD) and productivity dynamics. The tool accommodated a broad spectrum of stakeholder needs, facilitating decision-making across multiple scales and sectors.

The primary objective of PRAGA is to map spatial and temporal trends in ecological condition and LD, incorporating the knowledge, perceptions, and observations of local land users. Integrating such insights with biophysical data ensures that assessments reflect both ecological realities and stakeholder perspectives. After synthesis, this provides a decision-support tool for a broad range of stakeholders. Actions are guided by the LD response hierarchy—Avoid > Reduce > Reverse—with prioritization given to "Avoid" and "Reduce". This framework helps provide an optimal mix of actions, supporting the goal of land degradation neutrality (LDN) while ensuring no net loss of ecosystem function.

For Georgia, the methodology was adapted to the specific context, and the priorities of national and local stakeholders. These adaptations were implemented within the project “Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality Targets of Georgia through Restoration and Sustainable Management of Degraded Pasturelands (MSP),” which aimed to support Georgia in meeting its LDN targets through the restoration and sustainable management of degraded pasture ecosystems.

Implementation followed a specifically developed stepwise manual. This focused on capacity building for the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia (MEPA), enabling them to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of decision-making processes within the project-developed Municipal Pasture Planning (MPP) approach.

Stakeholder engagement included a broad spectrum of actors: pasture users, representatives from national, municipal, and town-level administrations, technical staff, NGOs, conservation organizations, and neighbouring communities. All participants played an active role by contributing qualitative insights and field-based observations related to: a) the current condition of pastures, b) observed ecological changes and pasture evolution, c) the extent and severity of land degradation, including the mapping of both high-quality and degraded areas, d) perceived impacts of management practices on landscape health, e) recommendations for actions needed to conserve or improve rangeland conditions and f) identification of context-specific indicators to capture ecological and productivity trends.

Pastureland users have long expressed concern over the decline in quality and extent of communally managed grasslands. Their familiarity with the landscape enables them to accurately identify and map areas affected by degradation. This project empowered local communities and national stakeholders to define and prioritize context-specific indicators of land health and degradation. The resulting information was provided to the Municipal Pasture Working Groups, serving as a critical platform for articulating priorities and guiding public investment decisions aimed at combating land degradation. Given the history and pastoral resources currently found in Georgia’s rural areas, the project piloted the use of a Controlled Grazing technology as a means to more efficiently utilise grazing and animal impact as a tool to conserve and restore pasturelands and biodiversity at scale. PRAGA is well suited to serve as a feedback loop to determine trends and achievement towards these goals.

2.3 Photos of the Approach

General remarks regarding photos:

Stakeholder inputs not only enhanced the interpretation of remote sensing data but also fostered greater local engagement with land conditions through the participatory framework of the PRAGA methodology. This approach provided a platform for diverse stakeholder groups and land users to communicate priorities and observed trends, thereby strengthening collective investment in sustainable land management.

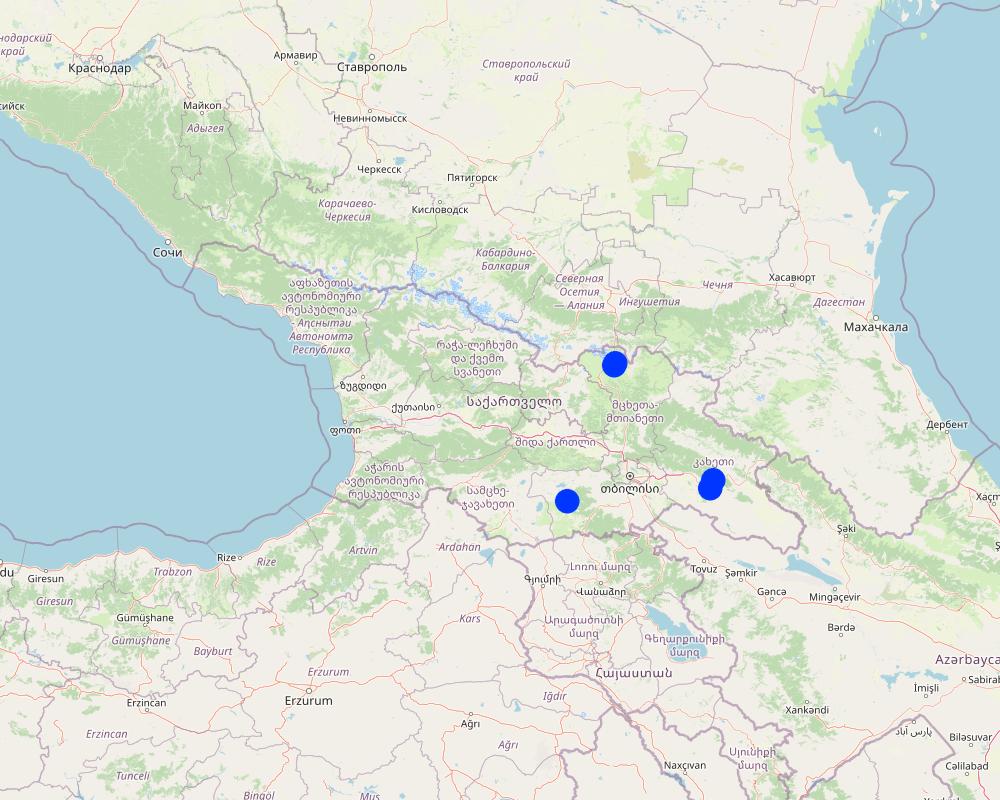

2.5 Country/ region/ locations where the Approach has been applied

Country:

Georgia

Region/ State/ Province:

Dmanisi, Gurjaani and Kazbegi Municipalities

Further specification of location:

Ganakleba, Naniani, Sno

Comments:

The project developed an adapted PRAGA methodology through a collaborative process involving the Georgian Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture (MEPA), relevant NGOs, and national experts. A stepwise manual was produced to guide the application of the approach at the municipal level in the three pilot sites of Dmanisi, Gurjaani, and Kazbegi. The resulting datasets were integrated into an online platform built on the Trends.Earth framework, enabling multi-layered visualization and analysis of land degradation and ecological trends. The PRAGA assessment reports generated through this process are designed to support evidence-based decision-making within participatory Municipal Pasture Planning (MPP) approach established by the project, thereby facilitating direct engagement between land users and local authorities across the three municipalities.

Map

×2.6 Dates of initiation and termination of the Approach

Indicate year of initiation:

2019

Year of termination (if Approach is no longer applied):

2025

Comments:

The baselines were established in 2019, with stakeholder workshops and development of the adapted methodology which culminated in the stepwise manual. The manual was trialled in the 3 participant Municipalities in 2024 and 2025, with field surveys being conducted annually.

2.7 Type of Approach

- project/ programme based

2.8 Main aims/ objectives of the Approach

The approach functions as a participatory baselining and monitoring system designed to quantify ecological health and land degradation by measuring the three United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator 15.3.1 components: land cover change, land productivity (via Net Primary Production), and carbon stocks (through Soil Organic Carbon assessment). It also incorporates supplementary national and sub-national indicators as indicated in the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) Conceptual Framework. The resulting data is institutionally integrated with Municipal Pasture Planning approach and disseminated to community-level actors implementing Controlled Grazing and other Sustainable Land Management (SLM) practices. Consequently, this system operates as an information feedback loop within a broader LDN response mechanism. If scaled nationally across all Georgian municipalities, it has the potential to serve as the official LDN Target monitoring and reporting framework, linking ground-level observations and interventions with municipal budgeting processes and enabling prioritised, stakeholder-supported investments to expand nature-based solutions.

Further details can be found in the referenced articles at the end of this document.

2.9 Conditions enabling or hindering implementation of the Technology/ Technologies applied under the Approach

social/ cultural/ religious norms and values

- enabling

From both cultural and management perspectives, rural Georgians maintain a strong connection to their landscape and possess valuable knowledge of ecological processes and land degradation. The PRAGA methodology integrates this local insight by incorporating their perspectives on ecological dynamics, natural capital, and context-specific indicators to effectively monitor environmental change and degradation.

availability/ access to financial resources and services

- enabling

Over the past 15 years, Georgia’s decentralization reforms have increased local governments’ access to financial resources, mainly through shared VAT revenues, more control over municipal property, and expanded local fees. These changes have improved the ability of many municipalities to plan budgets and provide services, though results vary widely by region.

- hindering

Local governments in Georgia still depend heavily on central transfers, face unequal administrative capacity, and often lack the technical or financial expertise needed to fully manage newly devolved powers. Political reversals, slow implementation of promised reforms, and inconsistencies in transferring property and competencies have further hindered the decentralization process.

institutional setting

- enabling

Georgia’s legal framework for local self-government gives municipalities formal responsibilities over land use and environmental management, which supports the creation of a land-degradation monitoring system. Recent decentralization reforms and increased municipal revenues provide a stronger resource base for building such capabilities. In addition, Georgia’s national environmental reporting obligations and expanding digital tools create opportunities for municipalities to integrate into broader, data-driven monitoring structures.

- hindering

Many municipalities still lack the funding, technical capacity, and skilled staff needed to operate a robust land-degradation monitoring system. Responsibilities for land and natural resources remain fragmented across national agencies, making data access and coordination difficult. Political centralization and uneven municipal capabilities further limit long-term, locally driven environmental monitoring efforts.

collaboration/ coordination of actors

- enabling

Georgia has formal coordination mechanisms—such as inter-ministerial councils and the Climate Change Council—that bring central ministries and municipalities into shared decision-making processes. Ongoing decentralization and UNDP-supported governance reforms have strengthened institutional linkages and improved communication between government levels. Expanding digital systems and data platforms further support smoother information sharing, which helps agencies coordinate more effectively across sectors and jurisdictions.

- hindering

Interagency collaboration in Georgia is weakened by the temporary nature of many coordination bodies, which limits consistency and long-term cooperation. Local governments often lack the technical capacity and resources needed to participate effectively in complex national initiatives. Fragmented responsibilities across ministries and persistent centralization trends further complicate data sharing, decision-making, and coherent policy implementation.

legal framework (land tenure, land and water use rights)

- enabling

When implemented correctly, the PRAGA approach is non-invasive, nor does it depend on classified remote sensing data. Prior to any field sampling, appropriate access rights must be secured. Stakeholder engagements and participatory mapping exercises were conducted by experienced facilitators, with assurances of fair and equitable treatment upheld by the project’s implementing partners.

policies

- enabling

The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia (MEPA) — together with national and international experts and key stakeholders — has developed the National Policy Concept for Sustainable Pasture Management, laying out a comprehensive framework for pasture identification, zoning, classification and sustainable use, including common-use regimes, leasing arrangements, and regulated grazing. This policy concept is being formulated under the “Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality” project, supported by the FAO, REC Caucasus and CENN. The concept serves as the basis for a draft Law on Pasture Management, currently under discussion as of mid-2024, which aims to formalize pasture management regimes, protect biodiversity, prevent degradation, and support livestock-based livelihoods. The process signals that the Georgian Government is actively establishing a policy and legal environment intended to safeguard Georgian grasslands and uphold their associated livelihoods and heritage.

land governance (decision-making, implementation and enforcement)

- enabling

Developing the National Pastureland Management Policy Concept and the forthcoming Law on Pasture Management will significantly clarify land rights, responsibilities, and access arrangements for Georgia’s pasture users. It would strengthen coordination among national and municipal institutions, establish evidence-based pasture planning, and improve transparency through better data and mapping systems. These reforms would reduce land-use conflicts, enhance accountability, and support sustainable livestock-based livelihoods. Overall, they would shift land governance toward a more coherent, transparent, and environmentally grounded system that protects both ecosystems and rural communities.

- hindering

Current land governance in Georgia limits proper land management because it is fragmented, poorly coordinated, and weakly grounded in ecological data. Unclear tenure, incomplete monitoring systems, and weak enforcement create conditions where pasture degradation can proceed unchecked, making it difficult to achieve land degradation neutrality or evidence-based ecological management.

knowledge about SLM, access to technical support

- hindering

The implementation of PRAGA requires a team of well-trained specialists, typically coordinated by a well-resourced organization, often in partnership with government or official agencies, to oversee data collection, analysis, and reporting. This multidisciplinary team would generally include botanists or ecological monitoring experts, remote sensing analysts, statisticians, and professional facilitators. Certain components, such as laboratory analysis of soil samples and graphic design for publications, may require outsourcing to external service providers.

workload, availability of manpower

- enabling

The analyses required by PRAGA are straightforward and replicable by most professionals within their respective fields.

other

- hindering

Collecting data on the scale and intensity of land degradation is inherently valuable for guiding decision-makers in navigating complex environmental and socio-economic contexts. However, publicly mapping land degradation can be politically sensitive, as it may expose contested land use issues or governance challenges. Such sensitivities can impede the adoption and implementation of land degradation mapping protocols and associated management interventions.

3. Participation and roles of stakeholders involved

3.1 Stakeholders involved in the Approach and their roles

- local land users/ local communities

Pasture and grassland users (private, de jure and de facto tenure situations), local livestock owners and producers, local villagers

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, participate in mapping sessions and locate areas on maps, participate in monitoring feedback sessions as required in the Municipal Pasture Planning.

- community-based organizations

Community resource management groups and/or conservation groups, special interest groups, both formal and informal

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, participate in mapping sessions and locate areas on maps, participate in monitoring feedback sessions as required in the Municipal Pasture Planning.

- SLM specialists/ agricultural advisers

Ministerial and Governmental Agencies, Agricultural Extension Workers, Land Management specialist

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, participate in mapping sessions and locate areas on maps, participate in monitoring feedback sessions as required in the Municipal Pasture Planning.

- researchers

Academic and State-funded research institutions

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, speak to ecological trends and data layers of interest that could be incorporated into remote sensing requirements

- NGO

National and regional NGO

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, provide support to PRAGA sponsored events and outreach programmes to ensure all relevant stakeholders can participate and have their voice shared.

- private sector

Private sector livestock producers, livestock sector and value chain representatives

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, review PRAGA reports and analyse how their decisions affect land management processes within their local product value sheds.

- local government

Local administrations and officials

Define the state of degradation of land, define contextually relevant indicators for determining land degradation, review PRAGA reports and analyse how their policies affect land management processes within their mandated boundaries. Actively organise and participate in monitoring feedback sessions as required in the Municipal Pasture Planning.

- national government (planners, decision-makers)

Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia, State Agency on Land Sustainable Management and Land Use monitoring (NASLM)

Funding and supervision of the implementation of the Participatory Assessment of Land Degradation and Sustainable Land Management in Grasslands and Pastoral Systems (PRAGA), in addition to the publication the results to support Municipal Pastureland Planning sessions. Maintain online tools for reviewing PRAGA data if deemed useful, or explore alternative platforms to share and engage the public on this information and Georgia’s progress toward Land Degradation Neutrality.

If several stakeholders were involved, indicate lead agency:

Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia

3.2 Involvement of local land users/ local communities in the different phases of the Approach

| Involvement of local land users/ local communities | Specify who was involved and describe activities | |

|---|---|---|

| initiation/ motivation | interactive | Both de jure and de facto users of communally managed grasslands demonstrated strong concern and actively voiced their observations regarding land degradation processes affecting Georgian pastures. The PRAGA methodology effectively captures these local insights, integrating them into a participatory monitoring system that informs decision-making at local, regional, and national levels. This system is specifically designed to support the monitoring of Georgia’s Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) targets related to grasslands. |

| planning | interactive | The PRAGA methodology utilizes participatory mapping and facilitated stakeholder interventions to identify hotspots of land degradation as well as areas of high biodiversity value and sustainable land management (SLM). This locally sourced information is crucial for guiding field monitoring efforts and calibrating remote sensing analyses. |

| implementation | external support | Implementation and funding of the PRAGA approach are generally provided by projects or government agencies. Given the scale of the methodology—particularly the remote sensing component—as demonstrated in the Georgian case, it is unlikely that a community would benefit from implementing PRAGA independently using its own resources. For community-level monitoring, other tools and protocols better suited to smaller scales are typically more appropriate. |

| monitoring/ evaluation | interactive | In Georgia, the PRAGA methodology was integrated as the monitoring and evaluation component of a broader Decision Support System (DSS) designed to underpin local pasture-level planning and municipal pasture planning protocols. Local land users, being the most intimately connected to the landscape, are well positioned to implement Sustainable Land Management (SLM) practices that address degradation identified through PRAGA’s participatory approach. If scaled nationally, this DSS could establish a comprehensive linkage between grassroots stakeholders and ministerial authorities, fostering coordinated land degradation management across all levels. |

3.3 Flow chart (if available)

Description:

Simplified overview of how PRAGA (or other LDN/land based monitoring systems) information supports the application of the LDN Conceptual Framework and how these results link to planning process and application of selected SLM technologies, such as Controlled Grazing (Regional Environmental Centre for the Caucasus, 2025).

3.4 Decision-making on the selection of SLM Technology/ Technologies

Specify who decided on the selection of the Technology/ Technologies to be implemented:

- all relevant actors, as part of a participatory approach

Explain:

PRAGA is a monitoring tool and supports the correct application of Controlled Grazing and other SLM technologies or practices, by providing data on soil surface conditions and pasture health and productivity.

Specify on what basis decisions were made:

- evaluation of well-documented SLM knowledge (evidence-based decision-making)

- personal experience and opinions (undocumented)

- Results from PRAGA application at pasture unit and Municipal scales

4. Technical support, capacity building, and knowledge management

4.1 Capacity building/ training

Was training provided to land users/ other stakeholders?

Yes

Specify who was trained:

- land users

- field staff/ advisers

- State Agency on Land Sustainable Management and Land Use monitoring (NASLM).

If relevant, specify gender, age, status, ethnicity, etc.

Training was conducted at multiple levels. First, internal sessions were held to brief workstream team leaders and technicians in the State Agency on Land Sustainable Management and Land Use monitoring (NASLM) about the technical and methodological requirements of PRAGA. These included calibration exercises for the field survey process and detailed discussions with GIS specialists on the selection and integration of data layers into the Trends.Earth platform. Second, targeted training was provided to facilitators responsible for leading stakeholder monitoring and evaluation sessions, with a focus on PRAGA’s specific mapping requirements.

Additionally, stakeholders received an introductory session on participatory mapping and the overall objectives of the PRAGA methodology. This session outlined how participatory mapping is used to identify areas of land degradation, biodiversity hotspots, SLM practices, and the intensity of land use and degradation across mapped areas.

Form of training:

- on-the-job

- courses

Form of training:

- Specialised sessions and workshops

Subjects covered:

Training Focus Areas by Stakeholder Group

1. Field Survey Monitors

Site selection protocols

Calibration of survey scoring methods

Data entry procedures using project-specific spreadsheets

2. GIS Experts / State Agency on Land Sustainable Management and Land Use monitoring (NASLM)

GIS requirements aligned with the Good Practice Guidance (GPG) and supported by local datasets and analysis

Integration of participatory mapping outputs and field survey data into spatial analysis workflows

3. PRAGA Facilitators

a) Overview of the PRAGA methodology and its operational framework

b) Techniques for leading effective participatory mapping sessions

c) Processes for data collection, documentation, and reporting

4. Stakeholder Groups (e.g., land users, community representatives, local officials)

a) Introduction to PRAGA and its objectives

b) Role of participatory mapping in identifying land degradation and SLM practices

c) Explanation of LDN indicators and identification of relevant, locally appropriate indicators

Comments:

Effective implementation of the PRAGA methodology requires coordination across several distinct workstreams, as well as the capacity to process and translate collected data into user-friendly reports and interactive outputs. These deliverables are essential for supporting the Municipal Pasture Planning approach developed under the GCP/GEO/006/GFF project.

4.2 Advisory service

Do land users have access to an advisory service?

Yes

- At Municipal offices and events

Describe/ comments:

Georgia's Rural Development Agency (RDA) and Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia (MEPA) provide agricultural extension services, while publicly subsidized technical assistance via the State Technical Assistance Program target cooperatives, associations or groups rather than individual smallholders, which may exclude small farms or transhumance herders.

4.3 Institution strengthening (organizational development)

Have institutions been established or strengthened through the Approach?

- yes, greatly

Specify the level(s) at which institutions have been strengthened or established:

- local

- regional

- national

Describe institution, roles and responsibilities, members, etc.

Through the PRAGA approach, local pasture users are empowered to voice concerns related to land degradation, invasive species encroachment, and land management practices. They can also spatially identify these issues on maps, providing first-hand insights into the extent, severity, and nature of changes in land health and use. This locally sourced information is systematically captured and integrated into ongoing assessment and monitoring feedback loops.

At the municipal level, local experts and administrators contribute additional knowledge on land use drivers and emerging trends, which are also mapped to ensure alignment with stakeholder perspectives.

At the National level, institution strengthening was achieved through a series of trainings to the NASLM specialists in order to strengthen NASLM capacity to support implementation of UNCCD requirements set out in the LDN principles and LDN oriented sustainable land management.

These participatory inputs are then compared and analysed alongside remote sensing data and field survey results. The combined findings are synthesized into a municipal-scale report, which can be visualized through an interactive online mapping tool based on Trends.Earth. This tool supports evidence-based decision-making within the Municipal Pasture Planning sessions.

Specify type of support:

- capacity building/ training

Give further details:

PRAGA requires investment in funding, training, and equipment; however, it remains a cost- and resource-efficient approach for monitoring land health trends across areas of up to 500,000 hectares. It is considered most effective for landscapes ranging between 5,000 and 120,000 hectares in size.

4.4 Monitoring and evaluation

Is monitoring and evaluation part of the Approach?

Yes

Comments:

This adapted PRAGA approach serves as the monitoring and reporting component within a broader planning and management framework designed to support the Sustainable Land Management (SLM) technology of Controlled Grazing. The overarching objective is to leverage Georgia’s livestock sector to contribute to the achievement of the country’s Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) targets and support the restoration of degraded grasslands. The data collected and analysed through PRAGA is compiled into detailed reports and delivered to the Municipal Pasture Working Groups established under the project “Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality Targets of Georgia through Restoration and Sustainable Management of Degraded Pasturelands” (GCP/GEO/006/GFF).

If yes, is this documentation intended to be used for monitoring and evaluation?

Yes

Comments:

Development of WOCAT articles was identified as part of the deliverables for the project 'Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality Targets of Georgia through Restoration and Sustainable Management of Degraded Pasturelands (GCP/GEO/006/GFF)', as a means to contribute lesson learnt and offer methods and approaches that can be adapted to other national contexts.

4.5 Research

Was research part of the Approach?

No

5. Financing and external material support

5.1 Annual budget for the SLM component of the Approach

If precise annual budget is not known, indicate range:

- 10,000-100,000

Comments (e.g. main sources of funding/ major donors):

Obviously costs range greatly as each context will have very different variables influencing costs. However, small areas of 5,000 ha can have costs of approximately $4.70 USD / ha, and decrease as area increases, with larger sites of above 100,000 ha being monitored or baselined for approximately $0.50 USD / ha.

Cost can also be expected to increase if capacity building and training of field monitors and facilitators is required.

5.2 Financial/ material support provided to land users

Did land users receive financial/ material support for implementing the Technology/ Technologies?

Yes

If yes, specify type(s) of support, conditions, and provider(s):

In the case of the Controlled Grazing technology pilots funded by the GCP/GEO/006/GFF project, a full list of materials and other forms of financial support is detailed and available in the published WOCAT article.

5.3 Subsidies for specific inputs (including labour)

- labour

| To which extent | Specify subsidies |

|---|---|

| fully financed | All field labour, facilitation of PRAGA sessions, GIS expertise and mapping outputs, as well as the development of the online mapping application, were funded by the GCP/GEO/006/GFF project. |

- equipment

| Specify which inputs were subsidised | To which extent | Specify subsidies |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring field kit | fully financed | Basic field equipment for monitoring was supplied, including GPS, plant identification manuals and off-road vehicles. |

Comments:

Participatory mapping and map validation workshops involved key stakeholders such as land users, town and municipal administrators, community representatives, and special interest groups. While participants were not compensated for their contributions, food and refreshments were provided during the sessions, funded by the GCP/GEO/006/GFF project.

5.4 Credit

Was credit provided under the Approach for SLM activities?

No

5.5 Other incentives or instruments

Were other incentives or instruments used to promote implementation of SLM Technologies?

Yes

If yes, specify:

Strengthening land tenure rights for land users and communities who demonstrate effective land management—verified through annual PRAGA assessments or other ecological monitoring methods—was a key project deliverable. This was successfully achieved at pilot sites, providing a scalable model for national-level implementation and an additional benefit for participant communities.

6. Impact analysis and concluding statements

6.1 Impacts of the Approach

Did the Approach empower local land users, improve stakeholder participation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The majority of Georgia’s grazing lands are state-owned, with land use often occurring under de facto tenure arrangements. Consequently, there are currently no established mechanisms for open dialogue regarding the condition and health of these grasslands or for discussing management needs and solutions to ensure their conservation and the sustainability of the livelihoods they support.

Did the Approach enable evidence-based decision-making?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The approach provided a wide range of information that was able to be graphically represented through maps and graphs, showcasing the state of land degradation balance at the Municipal scale. This was supported through land user participatory mapping sessions that often showed strong correlations between land user interpretations of land degradation and those identified through remote sensing and field surveys.

Did the Approach help land users to implement and maintain SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Ecological monitoring systems can be vital tools to reveal trends and inform decision-making. In the case of the pilot sites where Controlled Grazing was implemented, PRAGA was used to baseline and track progress towards improved pasture productivity and soil cover. It scaled well for different land use types and sizes.

Did the Approach improve coordination and cost-effective implementation of SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

It did in its capacity to provide data on the results of the Controlled Grazing trials, as well at the Municipal scale.

Did the Approach mobilize/ improve access to financial resources for SLM implementation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

No, and given the scale of monitoring conducted in the three participating municipalities—ranging from 84,000 to 120,000 hectares—numerous communities and land user groups were involved across diverse land tenure arrangements, potentially complicating access to financial resources and fiscal accountability.

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of land users to implement SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The approach provided a model for a feedback loop by which land users can understand landscape trends in land health and analyse how their management decisions are leading to the monitoring results. This allows for subsequent conversations on how to best address land degradation drivers and map potential solutions given resources available.

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of other stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Yes, the work undertaken created a valuable platform for diverse stakeholder groups to discuss land degradation and the challenges affecting Georgia’s pasturelands. Through participatory mapping, ecological monitoring and collaborative data analysis, stakeholders were actively engaged in identifying problems and sharing local knowledge. These interactive discussions generated lively exchange and fostered a shared understanding of the pressures facing pasture ecosystems. This collective recognition of challenges formed an essential foundation for the policy support and decision-making processes advanced through the project.

Did the Approach build/ strengthen institutions, collaboration between stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Yes, the PRAGA approach strengthened institutions and fostered collaboration by bringing together diverse stakeholders, principally land users who previously had limited opportunities to voice concerns or collectively engage in solutions, in addition to municipal authorities and community representatives.

Did the Approach mitigate conflicts?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Yes, the PRAGA approach can help mitigate conflicts by creating an inclusive platform where diverse stakeholders openly share their perspectives on land use, degradation, and management, as well as information and data that show trends rather than absolutes.

Did the Approach empower socially and economically disadvantaged groups?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Yes, the PRAGA approach empowered socially and economically disadvantaged groups, primarily small-scale livestock owners who rely on communal grasslands for grazing. By involving these stakeholders directly in monitoring and mapping pasture health and degradation, PRAGA gave them a platform to voice their concerns and influence decision-making. Their inclusion helps ensure that landscape health and pasture productivity, which are vital for their livelihoods, are prioritized in sustainable land management efforts.

Did the Approach improve gender equality and empower women and girls?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The PRAGA approach is developed to facilitate gender equality in reporting on land degradation issues and providing space for women and girls by actively participate in monitoring, mapping, and decision-making processes related to land management. In the case of Georgia, this was achieved and professionals and producers of both genders actively partook in project activities.

Did the Approach encourage young people/ the next generation of land users to engage in SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

As with gender, the PRAGA approach provides a equal platform for voicing opinions. Their was a reasonable degree of youth participation in the mapping events, though it should be said that the majority of participants and professionals that participated in project activities, such as PRAGA sessions, were middle aged or older.

Did the Approach improve issues of land tenure/ user rights that hindered implementation of SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

An ecological monitoring system like PRAGA can identify which land tenure situations demonstrate the highest rates of productivity and effective Sustainable Land Management (SLM). However, it would be inaccurate to claim that monitoring alone directly improves land tenure or land use rights. In the communities involved in this project, it was the combination of legal and technical support that played a crucial role in securing communal pastures by officially registering them under the Georgian National Cadastre as township property. This formal recognition provided land tenure security, which in turn significantly boosted local motivation to improve access and adopt SLM technologies such as Controlled Grazing, water harvesting, and woody weed eradication.

Did the Approach lead to improved food security/ improved nutrition?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The PRAGA approach indirectly contributes to improved food security and nutrition by promoting the sustainable management of pasturelands, which supports healthier and more productive grasslands. For instance, the rates of bare soil on grasslands is often linked to management decisions, and management that improved on pasture productivity was seen to provide for higher milking rates. Therefore, the link was made between monitoring, management and outcomes.

Did the Approach improve access to markets?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The PRAGA approach used by the project did not link ecological monitoring results with potential market incentives or premiums. Neither were any claims, either formal or informal, associated with the monitoring results.

Did the Approach lead to improved access to water and sanitation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

It sought to monitor ecological health of Georgian pasturelands, and was not specifically focused on water access and sanitation.

Did the Approach lead to more sustainable use/ sources of energy?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

No, the PRAGA approach did not directly lead to more sustainable use or sources of energy. Its primary focus is on land degradation monitoring and sustainable land management in pasture and grassland systems. While improved land management may have indirect environmental benefits, promoting sustainable energy use was not a core objective or outcome of the approach.

Did the Approach improve the capacity of the land users to adapt to climate changes/ extremes and mitigate climate related disasters?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Ecological monitoring at the field level requires a presence and close look at the results of management and the effects of management at the soil surface. This is not something that producers typically do and the process can be extremely effective. When monitoring becomes part of a scheduled and structured routine which include photo and data records, knowledge is gained which permits increased adaptability and resilience when faced with change.

Did the Approach lead to employment, income opportunities?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Yes, the PRAGA approach was shown to have the potential to create employment and income opportunities, particularly if implemented at the Municipal level. Its implementation would require a skilled workforce—including GIS specialists, statisticians, field biologists or botanists, certified facilitators, and government staff—to conduct data collection, analysis, reporting, and coordination with municipalities. These roles contribute to building a national monitoring system aligned with Georgia’s voluntary LDN targets, while also generating high-quality, stable employment in the environmental and land management sectors.

6.2 Main motivation of land users to implement SLM

- increased production

Improved pasture quality and quantity were key motivators for stakeholder participation and the adoption of Sustainable Land Management (SLM) technologies during the project. The field monitoring component of PRAGA was used at the pilot sites where Controlled Grazing was implemented to provide data for management and track project impact. Of special relevance to land users was data on the percentage of bare soil, presence of weed species and pasture palatability.

- reduced land degradation

The vast majority of stakeholders expressed serious concern over the condition of their community pasturelands. Large areas were dominated by low-quality grasses and forage species, alongside increasing encroachment by woody weeds. Infestations of Paliurus spina-christi were particularly problematic, posing significant ecological challenges and proving costly to remove. The Controlled Grazing technology was used as a means to control weed encroachment and maintain pasture health and fertility, while the PRAGA monitoring approach tracked progress towards these objectives and the pasture unit and municipal scales.

- environmental consciousness

The PRAGA approach was observed to environmental consciousness by directly engaging land users, local communities, and decision-makers in assessing and monitoring the condition of their landscapes and the extent and degree of land degradation of pasturelands. Through participatory mapping, field surveys, and discussion of ecological trends, stakeholders gain a clearer understanding of the causes and consequences of management practices.

- enhanced SLM knowledge and skills

Livestock herds using community pastures typically belong to two sub-groups: smallholder households with 1 to 3 dairy cattle, primarily for household consumption and occasional income, and larger-scale, more professional producers with greater capacity and motivation to adopt SLM technologies, such as Controlled Grazing. Despite differences in scale, both groups recognize the urgent need to improve pasture management due to the long-term decline in pasture extent and quality, as well as the growing impacts of climate change.

6.3 Sustainability of Approach activities

Can the land users sustain what has been implemented through the Approach (without external support)?

- no

If no or uncertain, specify and comment:

Effective implementation of the full PRAGA approach requires a well-funded coordinating entity with access to local datasets and the necessary technical expertise. This includes the involvement of GIS specialists to manage spatial data, skilled facilitators to lead participatory mapping sessions, and well-trained field monitors with a solid understanding of local pasture species. Reliable transportation, ideally with off-road capability, is also essential to reach remote monitoring sites. In addition, formal clearance from local administrators is required to access and conduct monitoring activities on state-owned lands. Together, these components ensure the accuracy, credibility, and smooth operation of the PRAGA methodology.

That said, the PRAGA field survey sheets are well adapted for use at the pasture unit scale for land managers, and together with a structured system of well sited and timed photos, it is capable of informing the application of the Controlled Grazing technology.

6.4 Strengths/ advantages of the Approach

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the land user’s view |

|---|

| PRAGA’s strengths lie in its participatory nature, giving local users a direct voice to express concerns about land degradation and management strategies and tools. |

| It empowers them to map and describe changes in their landscapes, tapping into their detailed knowledge of local conditions. This inclusive approach fosters ownership and accountability, while linking their observations to decision-making processes. |

| Additionally, PRAGA helps users better understand ecological trends and supports the sustainable management of pastures, which directly impacts their livelihoods. |

| Structured system of feedback and recommendations on investments focused on addressing land management, degradation and infrastructure through adequate use of community pasturelands at a Municipal scale. These recommendations are presented to the Municipal Pasture Planning sessions which includes a range of stakeholders, including representatives of local land users. |

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view |

|---|

| The methodology met expectations and objectives, in that it was capable of correctly identifying areas of degradation and increased ecological productivity in a highly cost-effective manner. |

| The methodology captured a variety of data trends across the entirety of the Municipalities where it was applied and has well-designed mechanisms for sharing the results and information through a simple to use online application based on TrendsEarth. |

| Areas where Land cover imagery and Public Cadastral records did not agree provided an opportunity to understand where the Public registry was incorrect or had not been updated to reflect current land use categories. |

| If this approach were scaled to cover the entire country of Georgia, it seems reasonable that it could provide a mechanism for reporting to the UNCCD on Georgia’s compliance with its National LDN Targets. |

| Integration of this approach is an important step in making Georgia’s LDN Target #1 Integrate LDN principles into national policies, strategies and planning documents a reality, which would contribute significantly to the GCP/GEO/006/GFF project’s objectives. |

6.5 Weaknesses/ disadvantages of the Approach and ways of overcoming them

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the land user’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

| The approach depends heavily on external funding and institutional support, which can make it uncertain or unsustainable in the long term from the users’ viewpoint. | To reduce dependence on external funding and support, developing partnerships with local government and institutions can help institutionalize PRAGA, or basic concepts and components, within existing frameworks. Exploring opportunities for community co-funding or cost-sharing can enhance sustainability. Building local capacity and leadership will gradually reduce reliance on external technical experts. |

| From the land users’ perspective, PRAGA’s disadvantages may include the need for ongoing time and effort to participate in mapping and monitoring activities, which can be challenging for those with limited resources or other pressing daily responsibilities. | To mitigate the time and effort burden on land users, participatory activities should be scheduled at convenient times to minimize disruption. Providing incentives such as refreshments, travel reimbursements, or small stipends can encourage participation, and simplifying data collection processes can reduce complexity and time demands. |

| There may also be concerns about how their input is used or whether it will lead to real change, potentially causing frustration if feedback doesn’t translate into improved management or support. | To address concerns about impact and follow-up, it is important to establish clear communication channels that regularly update land users on how their input is being used. Involving land users in decision-making processes can increase their sense of ownership and trust. Additionally, demonstrating tangible outcomes from the monitoring activities, such as visible improvements or targeted investments, helps build confidence in the process. |

| Some users might feel excluded if they lack training or confidence to engage fully in the technical aspects of the process. | Ensuring inclusion and capacity building involves providing training sessions tailored to different literacy and technical skill levels, so all users can engage meaningfully. Utilizing local facilitators who are trusted by the community encourages participation and builds confidence. It is also essential to ensure gender and social inclusion so marginalized groups feel empowered to contribute. |

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

| There is a clear relation to the number of field sites assessed and the quality of the resulting data. The number of sites must be considered from an economic, as well as a logistical and social (trained human resources) perspectives. Experience in other Central Asian and European contexts has shown that the funding entity and amount is largely the principal driver that determines the scope and range of the field work campaign to be conducted. | Adequate funding to ensure statistically relevant, random field sampling campaigns |

| There is a high risk that the PRAGA approach described here and the ensuing Municipal Pasture Working Groups established through this project will not continue or be scaled to cover all municipalities in Georgia. This is largely due to potential cost of scaling this to a national level which would need to be included in national budgets and potential institutional complexity of keeping the Municipal Pasture Working Groups (the principal focus of the annual PRAGA reports) functional across Georgia's 69 Municipalities. | Continue to demonstrate the value / cost-benefits of large scale ecological monitoring systems, that include well developed pathways for this information to inform on-ground activities and decisions by land users. |

| Another risk is a simplification of the PRAGA approach to only consider readily available desktop datasets, such as satellite imagery and data, without systems to integrate field data with local perceptions and experiences of land degradation. Interaction and engagement with local land users is | Continue to demonstrate the importance of participatory processes that involve land users as land users and locals are highly knowledgeable about ecological trends and are ultimately required for SLM solutions to be correctly implemented and maintained. |

7. References and links

7.1 Methods/ sources of information

- field visits, field surveys

Field sample baselines per Municipality were set in 2019 at 4 monitoring sites and repeated annually until 2025, totalling 24 field work sampling sessions (4 sites x 6 years = 24)

- interviews with land users

As a participatory approach, PRAGA interviews with land users were conducted during baselining and annual field surveys, participatory mapping workshops and PRAGA report and map validation exercises. It is estimated that approximately 100 people per Municipality were interviewed, giving a project total for PRAGA of 300 people.

- interviews with SLM specialists/ experts

Local administrations and agricultural extension agents, in addition to Ministerial officials/technicians and representatives from relevant NGOs were all consulted as part of the PRAGA interview process in participatory workshops.

- compilation from reports and other existing documentation

The PRAGA approach is designed to integrate existing reports, maps, and documentation wherever possible. By drawing on national datasets, cadastral information, land use records, and previous ecological assessments, PRAGA strengthens its analysis and avoids duplicating efforts. This integration ensures that local knowledge is complemented by official data sources, providing a more accurate and context-specific understanding of land degradation and sustainable land management (SLM) practices. It also helps align PRAGA outputs with national monitoring frameworks and reporting obligations, such as those related to SDG Indicator 15.3.1 and Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) targets.

7.2 References to available publications

Title, author, year, ISBN:

FAO and IUCN. 2022. Participatory rangeland and grassland assessment (PRAGA) methodology. First edition. Rome, FAO and Gland, IUCN

Available from where? Costs?

FAO Knowledge Repository, free of charge

Title, author, year, ISBN:

Sharpe, N., Mwangi, P., Isakov, I. and Onyango, V. 2022. Application of the participatory rangeland and grassland assessment (PRAGA) methodology in Kyrgyzstan – Baseline analysis, remote sensing, field assessment and validation report. Rome, FAO

Available from where? Costs?

FAO Knowledge Repository, free of charge

Title, author, year, ISBN:

Onyango, V., Masumbuko, B., Somda, J., Nianogo, A. and Davies, J. 2022. Sustainable land management in rangeland and grasslands. Working paper. Rome, FAO and Gland, Switzerland, IUCN

Available from where? Costs?

FAO Knowledge Repository, free of charge

Title, author, year, ISBN:

Onyango, V., Davies, J., Sharpe, N., Maiga, S.I., Ogali, C., Perez-Rocha, J. and Isakov, A. 2021. Land degradation neutrality: A rationale for using participatory approaches to monitor and assess rangeland health. Rome, FAO and IUCN

Available from where? Costs?

FAO Knowledge Repository, free of charge

7.3 Links to relevant information which is available online

Title/ description:

Participatory rangeland and grassland assessment (PRAGA) methodology. First edition.

URL:

https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/1e082d6c-bf65-46c5-80ba-ff3f5ec1548a

Title/ description:

Sustainable land management in rangeland and grasslands Working paper.

URL:

https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/8c90bdc0-071c-43ad-842d-12ec8e38ce14?utm=

Title/ description:

Land degradation neutrality A rationale for using participatory approaches to monitor and assess rangeland health

URL:

https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/57c52d95-6f46-4824-8938-88013046d560

Title/ description:

Application of the participatory rangeland and grassland assessment (PRAGA) methodology in Kyrgyzstan – Baseline analysis, remote sensing, field assessment and validation report, Sharpe et al., 2022

URL:

https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4f3c8468-4685-4bf5-a377-284acb62baff/content

Title/ description:

Terminal evaluation of the project "Participatory assessment of land degradation and sustainable land management in grassland and pastoral systems"

URL:

https://www.unevaluation.org/member_publications/terminal-evaluation-project-participatory-assessment-land-degradation-and-0

Title/ description:

PRAGA for LDN and Sustainable Rangeland Management Good Practices

URL:

https://wocat.net/documents/1267/Presentation_Bora_Masumbuko.pdf

Links and modules

Expand all Collapse allLinks

Controlled Grazing [Georgia]

“Controlled Grazing” seeks to harness the behaviours and habits of ruminant livestock to enhance three key ecological functions, namely the removal of plant biomass (grazing), soil and vegetation disturbance (animal impact) and increased nutrient cycling (dung and urine), with the goal of increasing perennial grass establishment, pasture palatability and reducing …

- Compiler: Nicholas Euan Sharpe

Modules

No modules