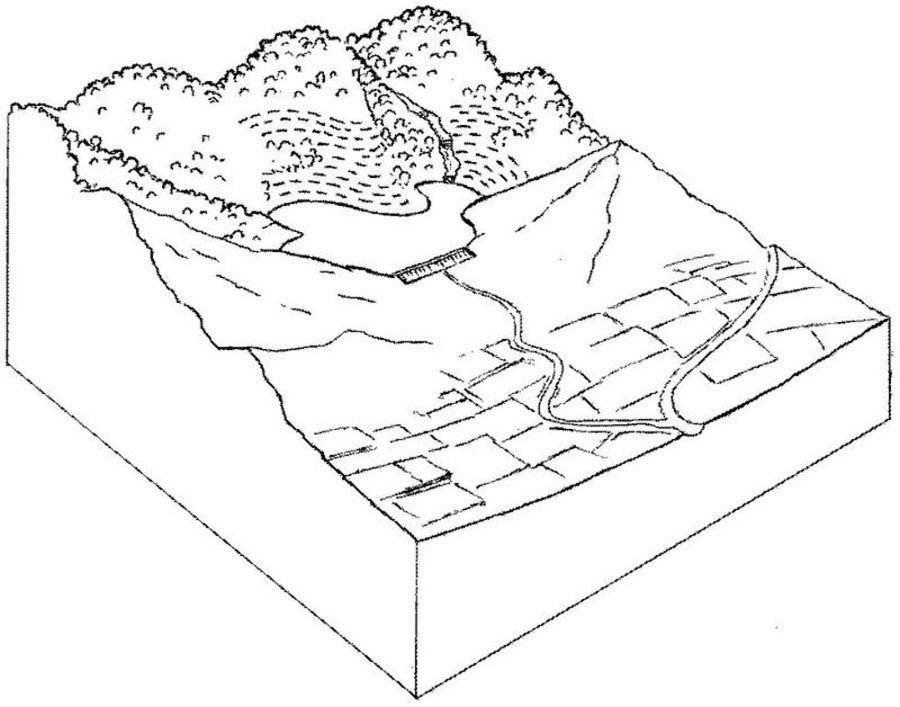

Forest catchment treatment aims to achieve production and environmental benefits through a combination of structural, vegetative and management measures in badly degraded catchments above villages. These efforts are concentrated in the highly erodible Shiwalik Hills at the foot of the Himalayan range where soil erosion has ravaged the landscape, and the original forest has almost disappeared.

The purpose of forest catchment treatment is first to rehabilitate the forest through protection of the area by ‘social fencing’ (villagers agreeing amongst themselves to exclude livestock without using physical barriers), then construction of soil conservation measures (staggered contour trenches, check dams, graded stabilisation channels etc; see establishment activities), and ‘enrichment planting’ of trees and grasses within the existing forest stand to improve composition and cover. These species usually include trees such as Acacia catechu and Dalbergia sissoo, and fodder grasses - as well as bhabbar grass (Eulaliopsis binata), which is used for rope making. The combined measures are aimed at reestablishing the forest canopy, understorey and floor, thereby restoring the forest ecosystem together with its functions and services. Biodiversity is simultaneously enhanced.

The second main objective is to provide supplementary irrigation water to the village below through construction of one, or more, earth dams. The village community - organised into a Hill Resource Management Society - is the source of highly subsidised labour for forest catchment treatment. After catchment protection around the proposed dam site(s), the dam(s) and pipeline(s) are constructed. The dams are generally between 20,000 and 200,000 m3 in capacity, and the pipelines usually one kilometre or less in length.

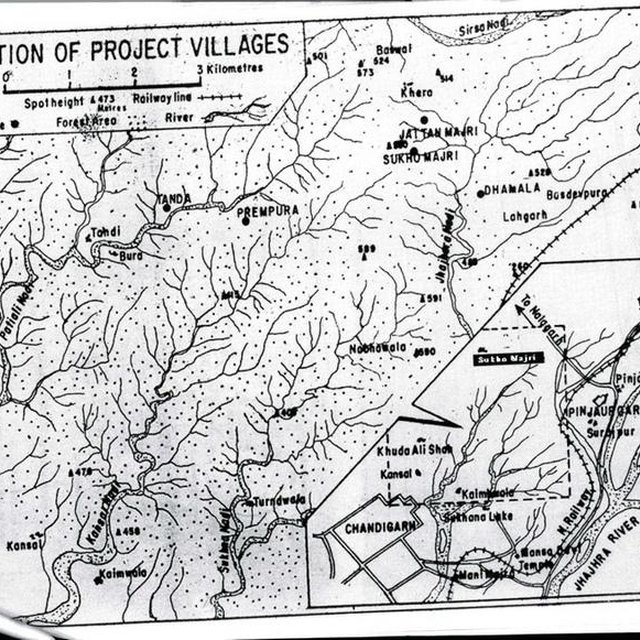

Apart from irrigation, the villagers benefit from communal use of non-timber forest resources. Forest catchment treatment (associated with the approach termed ‘joint forest management’ - JFM) has been developed from a pilot initiative in Sukhomajri village in 1976, and has spread very widely throughout India. This description focuses on Ambala and Yamunanagar Districts in Haryana State.

The Shiwalik hills where the SWC technology was applied is one of the eight most degraded, rainfed agro-ecosystems of India. It is highly erodible, with presence of low water retentive soils and severe soil erosion, haing water scarcity despite average 1000 mm annual rainfall.

ទីតាំង: Ambala and Yamunanagar, Haryana, ប្រទេសឥណ្ឌា

ចំនួនទីកន្លែងបច្ចេកទេស ដែលវិភាគ:

ការសាយភាយនៃបច្ចេកទេស:

តើស្ថិតក្នុងតំបន់ការពារអចិន្ត្រៃយ៍?:

កាលបរិច្ឆេទនៃការអនុវត្ត:

ប្រភេទនៃការណែនាំឱ្យអនុវត្តន៍៖

| បញ្ជាក់ពីធាតុចូល | ឯកតា | បរិមាណ | ថ្លៃដើមក្នុងមួយឯកតា (មិនមាន) | ថ្លៃធាតុចូលសរុប (មិនមាន) | % នៃថ្លៃដើមដែលចំណាយដោយអ្នកប្រើប្រាស់ដី |

| កម្លាំងពលកម្ម | |||||

| Labour | ha | 1,0 | 250,0 | 250,0 | 5,0 |

| សម្ភារៈ | |||||

| Machine use | ha | 1,0 | 75,0 | 75,0 | |

| សម្ភារៈដាំដុះ | |||||

| Seedlings | ha | 1,0 | 50,0 | 50,0 | |

| សម្ភារៈសាងសង់ | |||||

| Construction material for dam wall | ha | 1,0 | 25,0 | 25,0 | |

| ថ្លៃដើមសរុបក្នុងការបង្កើតបច្ចេកទេស | 400.0 | ||||

| ថ្លៃដើមសរុបក្នុងការបង្កើតបច្ចេកទេសគិតជាដុល្លារ | 400.0 | ||||

| បញ្ជាក់ពីធាតុចូល | ឯកតា | បរិមាណ | ថ្លៃដើមក្នុងមួយឯកតា (មិនមាន) | ថ្លៃធាតុចូលសរុប (មិនមាន) | % នៃថ្លៃដើមដែលចំណាយដោយអ្នកប្រើប្រាស់ដី |

| កម្លាំងពលកម្ម | |||||

| Labour | ha | 1,0 | 50,0 | 50,0 | 95,0 |

| ថ្លៃដើមសរុបសម្រាប់ការថែទាំដំណាំតាមបច្ចេកទេស | 50.0 | ||||

| ថ្លៃដើមសរុបសម្រាប់ការថែទាំដំណាំតាមបច្ចេកទេសគិតជាដុល្លារ | 50.0 | ||||

Increased non-timber forest products

Those with irrigation vs those without

Those with irrigation vs those without

Trees and grass

From new irrigation water