Keyhole Garden [Bangladesh]

- Creation:

- Update:

- Compiler: John Brogan

- Editor: Shahid Kamal

- Reviewers: Alexandra Gavilano, Deborah Niggli, Alvin Chandra, Joana Eichenberger

PUSTI BAGAN ("Garden for nutrition")

technologies_779 - Bangladesh

View sections

Expand all Collapse all1. معلومات عامة

1.2 Contact details of resource persons and institutions involved in the assessment and documentation of the Technology

SLM specialist:

Varadi Daniel

Greendots

Switzerland

SLM specialist:

Taylor Sheila

Send a Cow UK & Greendots

WASH Advisor:

Name of project which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Technology (if relevant)

Book project: where people and their land are safer - A Compendium of Good Practices in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) (where people and their land are safer)Name of the institution(s) which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Technology (if relevant)

Terre des Hommes (Terre des Hommes) - Switzerland1.3 Conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT

The compiler and key resource person(s) accept the conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT:

نعم

1.4 Declaration on sustainability of the described Technology

Is the Technology described here problematic with regard to land degradation, so that it cannot be declared a sustainable land management technology?

لا

1.5 Reference to Questionnaire(s) on SLM Approaches (documented using WOCAT)

Peer to Peer Pass-on Approach with Women [Bangladesh]

Terre des hommes and Greendots introduced the Peer to Peer pass-on system to enable women's groups in Bangladesh to spread the Keyhole Garden technique within their communities with the aim of enabling year-round homestead vegetable production despite the risk of flooding and tidal surge.

- Compiler: John Brogan

2. Description of the SLM Technology

2.1 Short description of the Technology

Definition of the Technology:

The Keyhole Garden model of homestead vegetable cultivation enhances the resilience of families living in areas with climate-related hazards, such as flooding and drought. Keyhole gardens have been shown to increase vegetable production in all seasons, thereby improving household food autonomy and dietary diversity.

2.2 Detailed description of the Technology

Description:

First initiated in Ugandan communities by Send a Cow UK, the keyhole garden technique is widespread in Africa. In 2011, Terre des hommes (Tdh) and Greendots piloted Keyhole Gardens for the first time in Asia, effectively adapting the design and methodology in Africa to the conditions of flood prone areas of Bangladesh, and eventually India. The garden is a good way to enhance dietary diversity, especially for poor/landless families.

Keyhole gardens consist of a raised circular garden made of clay, shaped like a horseshoe or keyhole, with a maximum diameter of approximately three meters. For flood prone areas in Bangladesh and India, the plinth height depends on the location and is typically the same as the house plinth to resist flooding. A compost basket is built at the center of the garden. Organic matter (kitchen cuttings) and residual water are added on a regular basis through the compost pit. In some countries, bricks or stones are used to make the plinth.

The keyhole garden is a typical Low External Input Sustainable Agriculture (LEISA) approach that includes integrated composting, water retention, use of local materials, natural pest and disease control techniques, natural soil fertility measures, and proximity to the kitchen for both harvesting and care of the garden. In regions with mild conditions of flooding, tidal surge and drought, the garden increases the duration of gardening period during the year thus reducing the risk of disaster. In the aftermath of cyclone Mahasen, keyhole gardens demonstrated DRR utility: although many were partially damaged, none had to be rebuilt entirely. Where plants did not survive the storm, users were able to sow seeds immediately. On the other hand, the traditional ground-level plots used for pit and heap gardening were completely flooded / waterlogged and unusable.

Benefits of the technology include: compact size, proximity to the household for convenient maintenance and harvesting, composting of kitchen cuttings in the basket; and an ergonomic structure (raised, accessible). The small size is also ideal to facilitate training on vegetable growing, soil fertility and pest & disease management to first-time gardeners and students in schools. Keyhole gardens are highly productive—in Lesotho a typical garden can satisfy vegetable needs for a family of eight persons (FAO, 2008). Combined, these factors are scalable as an appropriate technology for landless and marginal farmers. In Bangladesh, the gardens enabled families to produce vegetables even during the monsoon period. As the keyhole garden normally does not need to be rebuilt every year it is a more efficient technique in the long-term than traditional methods such as pit and heap.

Users say that their garden produce tends to be larger and tastier than conventional gardens or market produce; and many indicated that they were able to meet their own vegetable consumption needs and to sell surplus or gift vegetables. For some women it was difficult to access sufficient amounts of soil, which meant that they needed to walk long distances to build the plinth. (Fortunately many received support from other villagers.) Secondly, during the monsoon, while most of the land is flooded, the keyhole garden remains dry. Consequently, it may provide shelter to certain animals (e.g. rats) and attract higher number of pests. Regardless of these two limitations users agree that the benefits greatly

outweigh any observed limitations.

2.3 Photos of the Technology

2.4 Videos of the Technology

Comments, short description:

https://vimeo.com/44042261

The Keyhole garden was originally developed by African farmers to preserve their crops from the wind and the sand. Locally adapted in Bangladesh in Afzal’s vegetables garden with the help of Terre des hommes staff, the Keyhole garden can also protect the crops from the heavy monsoon rain and the salt water brought by flooding and storms. These literally destroy the crops. Widely adopted, it could help in preventing malnutrition by preserving the farmer's crops.

“Two days ago, my vegetable garden was wrecked by salt water and the monsoon rains”, says Afzal, who was the first person to test the new design proposed by Tdh and its technical partner Greendots. “The storm destroyed everything – except the keyhole garden, which is intact.”

Date:

14/06/2012

الموقع:

Patharghata, Barguna District, Barisal Division, Bangladesh

Name of videographer:

Julien Lambert, Image of Dignity

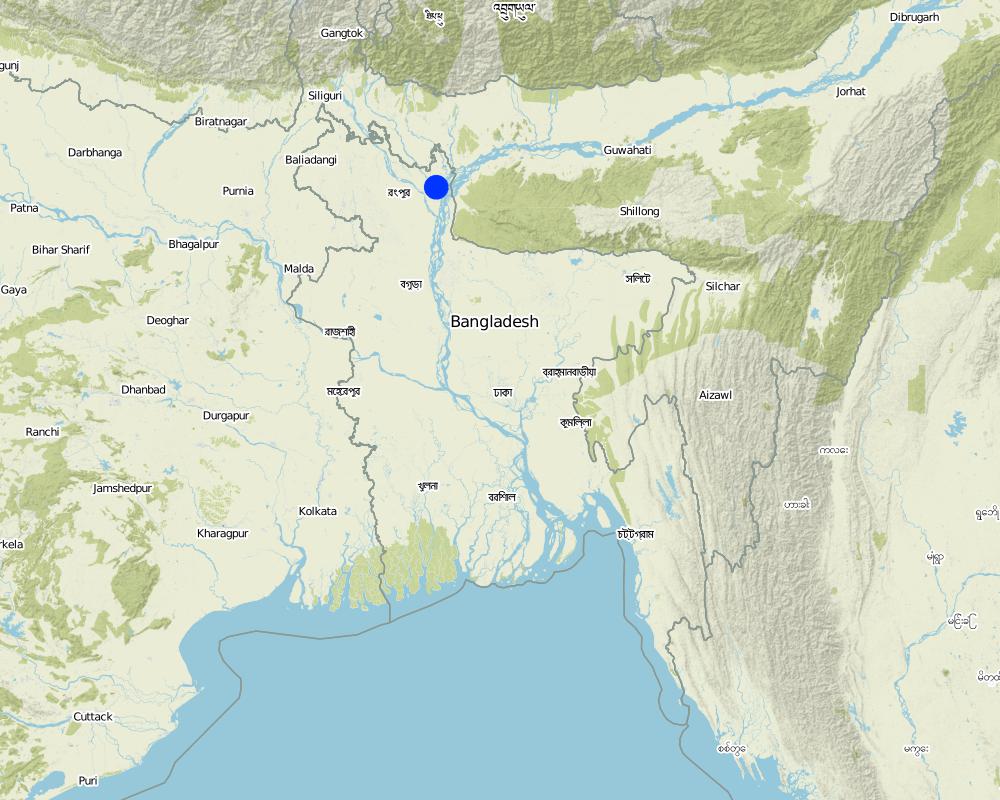

2.5 Country/ region/ locations where the Technology has been applied and which are covered by this assessment

بلد:

Bangladesh

Region/ State/ Province:

Kurigram District / Rajshahi and Barguna District / Barisal

Further specification of location:

Kurigram municipality (Kurigram), Patharghata Union (Barguna)

Specify the spread of the Technology:

- applied at specific points/ concentrated on a small area

Comments:

Kurigram and Pataharghata, Bangladesh

Applied in homesteads.

Map

×2.6 Date of implementation

Indicate year of implementation:

2012

2.7 Introduction of the Technology

Specify how the Technology was introduced:

- through land users' innovation

- during experiments/ research

- through projects/ external interventions

3. Classification of the SLM Technology

3.1 Main purpose(s) of the Technology

- improve production

- reduce risk of disasters

- adapt to climate change/ extremes and its impacts

- mitigate climate change and its impacts

3.2 Current land use type(s) where the Technology is applied

الأراضي الزراعية

- Annual cropping

- Perennial (non-woody) cropping

- Homestead Gardening

Annual cropping - Specify crops:

- cereals - quinoa or amaranth

- legumes and pulses - beans

- vegetables - leafy vegetables (salads, cabbage, spinach, other)

- vegetables - melon, pumpkin, squash or gourd

- vegetables - other

- vegetables - root vegetables (carrots, onions, beet, other)

- tomatoes, cauliflower, brocoli, watercress, eggplant, cucumber

Perennial (non-woody) cropping - Specify crops:

- medicinal, aromatic, pesticidal plants - perennial

- chili

Number of growing seasons per year:

- 3

حددها:

In Bangladesh the gardens produced in all seasons, with most challenges coming in the dry season due to soil salinity in some areas.

Is intercropping practiced?

نعم

Is crop rotation practiced?

نعم

If yes, specify:

Winter/Summer seasons

Comments:

Winter Season: red amaranth, spinach, green chilli, tomato, eggplant, carrot, radish, onion, garlic, country bean, pumpkin, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli.

Summer & Rainy Seasons: red amaranth, green amaranth, Indian spinach, Chinese watercress, green chili, okra, eggplant, yard long bean, bitter gourd, ash gourd, cucumber, pumpkin

3.3 Has land use changed due to the implementation of the Technology?

Waterways, waterbodies, wetlands

3.4 Water supply

Water supply for the land on which the Technology is applied:

- mixed rainfed-irrigated

3.5 SLM group to which the Technology belongs

- integrated soil fertility management

- integrated pest and disease management (incl. organic agriculture)

- home gardens

3.6 SLM measures comprising the Technology

agronomic measures

- A1: Vegetation/ soil cover

- A2: Organic matter/ soil fertility

structural measures

- S11: Others

3.7 Main types of land degradation addressed by the Technology

soil erosion by water

- Wt: loss of topsoil/ surface erosion

3.8 Prevention, reduction, or restoration of land degradation

Specify the goal of the Technology with regard to land degradation:

- prevent land degradation

- reduce land degradation

Comments:

See details in section 2.2

4. Technical specifications, implementation activities, inputs, and costs

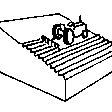

4.1 Technical drawing of the Technology

Technical specifications (related to technical drawing):

Gardens should be built in close vicinity to the beneficiary’s house, because gardens that are easily accessible and clearly visible are visited more regularly and maintained better.

The design is highly adaptable to local conditions and availability of free construction materials. The radius of the garden is 150CM and the delineated radius of the circular compost basket (in the center of the garden) is 45cm. The diagrams show (1) the location is near to house as an entry point for maintaining the garden; (2) the plinth is built to the same level of the house and a step is included where the plinth is high; (3) mulching to conserve the moisture; (4) interplanting a diversity of vegetables for both good vegetable health and good family nutrition; (5) using interplanted natural repellent plants as pest control for vegetables; (6) covering the basket during times of high sun intensity or heavy rain; (7) using liquid manures and plant teas as top dressing fertilisers.

Establishing what is the best height for your plinth very much depends on the local climatological conditions. In Bangladesh, the plinth is built from subsurface clayey soil, typically 2-3 feet in height - dependent on the location and level of seasonal flooding. The house plinth is a good gauge for how high to build the garden plinth. If the plinth is built too high, the roots of the plant will not be able to access sufficient water; and if built too low the next flood during the monsoon season may destroy the garden. Depending on dryness or soil/groundwater salinity, daily maintenance usually includes irrigating the soil. The outer rim of the plinth is protected with mud (and plastic or cloth) or stones. On top of the plinth is a mixture of soil and compost/manure (ratio 2:1) sloped up to the basket at a 30 - 40 degree angle. The central compost basket is filled with layers of fresh and dried vegetable matter, manure and ash to ensure that the soil fertility of the garden.

Women devised a number of different solutions to protecting the wall of the plinth and garden: Plastic bags, a combination of rice sacks (around the plinth edge) and plastic entrance way because of wear and tear (rice sacks erode faster), palm matting and old cloth. Some women put extra manure in the plinth walls to protect against flooding.

Sam Rich (www.fourthway.co.uk) has produced other technical drawings in addition to "How to Make Liquid Manure" such as: "How to make a Natural Pesticide" and "How to Make Plant Tea". There is also a version of the "How to Make a Keyhole Garden" in English from the experience in Africa.

Author:

Sam Rich: www.fourthway.co.uk

Date:

13/05/2012

4.2 General information regarding the calculation of inputs and costs

Specify how costs and inputs were calculated:

- per Technology unit

Specify unit:

Keyhole Garden

Specify currency used for cost calculations:

- USD

Indicate average wage cost of hired labour per day:

U.S.$2.50

4.3 Establishment activities

| Activity | Timing (season) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Clear land; mark out basket and external boundary using rope and stick pivoted from the centre) | Anytime |

| 2. | Build plinth (highest monsoon flood level+30cm); | Anytime |

| 3. | Construct basket at the centre from local materials. Fill basket with composting materials; | Anytime |

| 4. | Bring soil and heap it around the central basket. Any available animal dung can also be added into the soil mix for greater initial productivity. | Anytime |

| 5. | Plant vegetable seeds around the garden - a mix for good family nutrition and to stop the spread of pests and diseases; | According to the seasonal varieties |

| 6. | Mulch between plants to protect the soil. | Anytime |

| 7. | Protect the walls with rice sacks or other waterproof protection if neccessary. | Anytime |

4.4 Costs and inputs needed for establishment

| Specify input | Unit | Quantity | Costs per Unit | Total costs per input | % of costs borne by land users | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | Building the garden | person-days | 3,0 | 2,5 | 7,5 | 100,0 |

| Construction material | clay | 20,0 | ||||

| Total costs for establishment of the Technology | 7,5 | |||||

| Total costs for establishment of the Technology in USD | 7,5 | |||||

Comments:

Firstly, building the garden requires an initial investment in terms of labour and (locally available) inputs, such as soil and wood and clayey soil for the plinth (stones and bricks are frequently used for the plinth in Africa). These inputs are available on the homestead or in the community and generally free of cost. In rare cases families paid to have soil carted to their homestead, thus increasing the initial structural costs.

4.5 Maintenance/ recurrent activities

| Activity | Timing/ frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Weeding, harvesting, watering | Daily |

| 2. | Structural maintenance on the garden | Annual |

4.6 Costs and inputs needed for maintenance/ recurrent activities (per year)

| Specify input | Unit | Quantity | Costs per Unit | Total costs per input | % of costs borne by land users | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | Maintenance | person-days | 11,0 | 2,5 | 27,5 | 100,0 |

| Labour | Structural maintenance on the garden | person-days | 1,0 | 2,5 | 2,5 | 100,0 |

| Construction material | Earth Clay -depends on height: ex .4m plinth) | cubic meter | 11,0 | |||

| Construction material | Manure (quantity depends on design) | cubic meter | 2,0 | |||

| Construction material | Basket (sticks/bamboo with thin sticks to weave the basket | Sticks | 15,0 | |||

| Construction material | Protective material, rice bags/stones/plastic | Square meter | 18,0 | |||

| Total costs for maintenance of the Technology | 30,0 | |||||

| Total costs for maintenance of the Technology in USD | 30,0 | |||||

Comments:

In Bangladesh, women referred to the time spent working on the keyhole garden as “leisure time” and that they do this work after they have completed their domestic chores. Women estimated 45 minutes daily of such activity to maintain the garden. Calling it "leisure time" is misleading, but it suggests that most women generally enjoy working in the garden and do not regard it as heavy labour. The daily wage of an agricultural labourer differs per region. In Tdh's project area, wages are relatively low, especially for women. While male labourers may earn 200 BDT ($2.50) per day, women usually earn only 90 to 150 BDT. For the calculation, we applied the principle of equal pay for equal work, taking 200BDT per day.

4.7 Most important factors affecting the costs

Describe the most determinate factors affecting the costs:

Over the last few years, people in disaster-affecteed areas of Bangladesh have become familiar to receiving during humanitarian distributions; and expect “hand-outs” if they were to participate in a development project. The Keyhole garden project, however, follows the LEISA approach and does not rely on giving free inputs to the participants. (In a few cases where the local population was lacking seeds and experience in seed production, women's groups were given seeds and training.) A lack of reliance on external inputs or subsidies contributes to the sustainability of the project. The inputs (clay, manure, sticks, rocks, etc.) are locally available and usually do not require additional expenses. This may not be the case in all contexts.

5. Natural and human environment

5.1 Climate

Annual rainfall

- < 250 mm

- 251-500 mm

- 501-750 mm

- 751-1,000 mm

- 1,001-1,500 mm

- 1,501-2,000 mm

- 2,001-3,000 mm

- 3,001-4,000 mm

- > 4,000 mm

Specify average annual rainfall (if known), in mm:

2666,00

Specifications/ comments on rainfall:

Applied in areas with monsoon and drought like conditions in the project areas in Bangladesh.

Indicate the name of the reference meteorological station considered:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.PRCP.MM

Agro-climatic zone

- humid

- sub-humid

- semi-arid

The technology is adapted to semi-arid areas/countries in Africa like Uganda and Tanzania.

5.2 Topography

Slopes on average:

- flat (0-2%)

- gentle (3-5%)

- moderate (6-10%)

- rolling (11-15%)

- hilly (16-30%)

- steep (31-60%)

- very steep (>60%)

Landforms:

- plateau/plains

- ridges

- mountain slopes

- hill slopes

- footslopes

- valley floors

Altitudinal zone:

- 0-100 m a.s.l.

- 101-500 m a.s.l.

- 501-1,000 m a.s.l.

- 1,001-1,500 m a.s.l.

- 1,501-2,000 m a.s.l.

- 2,001-2,500 m a.s.l.

- 2,501-3,000 m a.s.l.

- 3,001-4,000 m a.s.l.

- > 4,000 m a.s.l.

Indicate if the Technology is specifically applied in:

- not relevant

5.3 Soils

Soil depth on average:

- very shallow (0-20 cm)

- shallow (21-50 cm)

- moderately deep (51-80 cm)

- deep (81-120 cm)

- very deep (> 120 cm)

Soil texture (topsoil):

- fine/ heavy (clay)

Soil texture (> 20 cm below surface):

- fine/ heavy (clay)

Topsoil organic matter:

- medium (1-3%)

5.4 Water availability and quality

Ground water table:

< 5 m

Availability of surface water:

excess

Water quality (untreated):

poor drinking water (treatment required)

Is water salinity a problem?

نعم

حددها:

In project sites along the Bay of Bengal

Is flooding of the area occurring?

نعم

Regularity:

frequently

5.5 Biodiversity

Species diversity:

- low

Habitat diversity:

- medium

5.6 Characteristics of land users applying the Technology

Sedentary or nomadic:

- Sedentary

Market orientation of production system:

- subsistence (self-supply)

- mixed (subsistence/ commercial)

Off-farm income:

- less than 10% of all income

- 10-50% of all income

Relative level of wealth:

- very poor

- poor

Individuals or groups:

- individual/ household

Level of mechanization:

- manual work

- animal traction

Gender:

- women

- men

Age of land users:

- middle-aged

Indicate other relevant characteristics of the land users:

Using a methodology called the problem tree analysis it is understood that the people living in the two working areas regularly experience health-related problems, economic challenges, and agricultural difficulties.

5.7 Average area of land used by land users applying the Technology

- < 0.5 ha

- 0.5-1 ha

- 1-2 ha

- 2-5 ha

- 5-15 ha

- 15-50 ha

- 50-100 ha

- 100-500 ha

- 500-1,000 ha

- 1,000-10,000 ha

- > 10,000 ha

Is this considered small-, medium- or large-scale (referring to local context)?

- small-scale

Comments:

The majority of the project beneficiaries are "landless" having access to small homestead areas and without cropland. Most households have access to small (< 16 decimal) or very small (< 6 decimal) homestead areas.

5.8 Land ownership, land use rights, and water use rights

Land ownership:

- individual, not titled

Land use rights:

- individual

Water use rights:

- open access (unorganized)

5.9 Access to services and infrastructure

health:

- poor

- moderate

- good

education:

- poor

- moderate

- good

technical assistance:

- poor

- moderate

- good

employment (e.g. off-farm):

- poor

- moderate

- good

markets:

- poor

- moderate

- good

energy:

- poor

- moderate

- good

roads and transport:

- poor

- moderate

- good

drinking water and sanitation:

- poor

- moderate

- good

financial services:

- poor

- moderate

- good

6. Impacts and concluding statements

6.1 On-site impacts the Technology has shown

Socio-economic impacts

Production

crop production

Quantity before SLM:

<5% of pilot families growing vegetables in all 3 seasons

Quantity after SLM:

50% of the pilot families able to grow vegetables in 3 seasons

Comments/ specify:

Before the project started, the majority of the participants were not able to produce vegetables year round. Especially during the monsoon months, people were dependent on produce available at the local market. The baseline survey indicated that in both regions more than 50% of the households would cultivate vegetables for a maximum of 3 months per year and in Kurigram 30% of the participants were not able to grow vegetables at all.

This situation has changed significantly after the introduction of the keyhole gardens. At least 50% of the households were able to produce vegetables during each season. Where in the past almost no one was able to cultivate during the monsoon period, now on average 63% of the households in Kurigram and 73% of the households in Patharghata were growing vegetables in the wet season.

The summer figures are actually lower than the monsoon figures. Seeds did not germinate well, because participants were not fully prepared to deal with the dry and saline conditions during this season. Learning from this experience, and with adequate support from Tdh, participants should be able to achieve higher cultivation rates in the future.

product diversity

Quantity before SLM:

Average of 2-4 types of vegetables grown.

Quantity after SLM:

Average of six types of vegetables grown

Comments/ specify:

During the field visits and individual interviews in June 2013, the majority of the participants indicated that in the keyhole garden they usually grow 6 or more different types of vegetables at any given time. This is a marked difference from previous years, when the majority of people in Patharghata would only grow 2 types of vegetables. In Kurigram the baseline was somewhat higher (31% cultivated 4 types of vegetables per year on average), but still significantly lower than in 2013. By increasing the different types of vegetables grown, the families have access to a more diversified diet.

production area

Quantity before SLM:

0

Quantity after SLM:

333

Comments/ specify:

In addition to the 175 pilot keyhole gardens, an additional 158 gardens were started on homesteads either via peer to peer pass-along system or spontaneous copy/replication of the technology.

Socio-cultural impacts

health situation

Comments/ specify:

The Keyhole Garden supports a diversified diet by enabling year-round vegetable production; thus boosting the resilience of homesteads exposed to extreme weather patterns (drought or monsoon/flood seasons).

situation of socially and economically disadvantaged groups

Comments/ specify:

Gardens will quickly increase household vegetable production, easing economic burden and providing for the household consumption or surplus to sell or gift. The latter can increase social bonding and benefit peer to peer linkages.

Teaching

Comments/ specify:

Keyhole garden building and maintenance teaches lessons of good soil, water and vegetable management that can be transferred to field crops or plain large scale vegetable growing.

Ecological impacts

Soil

soil loss

Comments/ specify:

Precious topsoil is not lost during flooding events.

Climate and disaster risk reduction

flood impacts

Comments/ specify:

Gardens that are not submerged by floods continue to produce in the monsoon season.

Other ecological impacts

Surpluses can be used for selling or gifting; increased vegetables especially at times when they are not usually available enables families to save money on expensive purchases out of the normal vegetable season

6.2 Off-site impacts the Technology has shown

Teaching

Comments/ specify:

Keyhole garden building and maintenance teaches lessons of good soil, water and vegetable management that can be transferred to field crops or plain large scale vegetable growing.

6.3 Exposure and sensitivity of the Technology to gradual climate change and climate-related extremes/ disasters (as perceived by land users)

Climate-related extremes (disasters)

Meteorological disasters

| How does the Technology cope with it? | |

|---|---|

| tropical storm | moderately |

| local thunderstorm | well |

Hydrological disasters

| How does the Technology cope with it? | |

|---|---|

| general (river) flood | very well |

| storm surge/ coastal flood | well |

Other climate-related consequences

Other climate-related consequences

| How does the Technology cope with it? | |

|---|---|

| reduced growing period | very well |

6.4 Cost-benefit analysis

How do the benefits compare with the establishment costs (from land users’ perspective)?

Short-term returns:

very positive

How do the benefits compare with the maintenance/ recurrent costs (from land users' perspective)?

Short-term returns:

very positive

Comments:

No long term study available.

In most cases no (or very low) investment cost in materials and a low investment cost in labor was necessary. Thus the establishment and maintenance costs are relatively low compared to the benefit of increased homestead vegetable production and access to produce for increasing dietary diversity. The benefit increases when the technology supports resilience to flooding as was the case from flooding (Kurigram), and partially from a cyclone (Patharghata).

6.5 Adoption of the Technology

- > 50%

If available, quantify (no. of households and/ or area covered):

333 from the pilot study. Subsequent projects by Tdh from 2013-2015 have seen over 3'500 keyhole gardens created in Bangladesh and India.

Of all those who have adopted the Technology, how many did so spontaneously, i.e. without receiving any material incentives/ payments?

- 91-100%

Comments:

All of the adopters did so with training but without inputs. Spontaneous adoption of the Keyhole Garden without training is not easy to measure, but Tdh's experience shows a conservative average of 11% (38 of 333 gardens).

6.6 التكيف

Has the Technology been modified recently to adapt to changing conditions?

نعم

If yes, indicate to which changing conditions it was adapted:

- climatic change/ extremes

Specify adaptation of the Technology (design, material/ species, etc.):

The technology was adapted from semi-arid zones in Africa (where soil amelioration and water conservation were priorities and materials such as stones and brick are available) to areas of South Asia prone to flood and tidal surge.

6.7 Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities of the Technology

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the land user’s view |

|---|

|

Seasonal local agriculturalists reported that gardens yielded high productivity with good vegetable quality and diversity; withstood heavy monsoon rains lasting for several days; and withstood a salt water tidal intrusion that destroyed adjacent traditional gardens. During the FGDs women clearly expressed a lot of enthusiasm for the project and all the participants indicated that they would continue with their garden, even if Tdh would no longer provide any support. One volunteer reported successfully harvesting five common vegetables usually impossible to grow in monsoon conditions: - In plain land we can cultivate once in a year but in keyhole garden we can harvest vegetables in three seasons and they don't go underwater in the rainy season - Save money for the family: don't need to buy fertilizers or vegetables and some people earn money by selling the garden product - We can collect vegetables for the children’s requirements directly from the garden when they need them - In a small space you can have lots of different vegetables and the taste is much better because the garden depends on compost – no chemicals - The cost to make is it very low, but you need labour; by our own labour we can build it - Because of composting the garden can always get nutrients |

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view |

|---|

|

The keyhole garden project has been very successful and has largely achieved its core objective to improve year-round access to nutritious food from the homestead area. These benefits are summarized again as: - Appropriate size for landless homesteads, also ideal to facilitate training on LEISA techniques to first-time gardeners and students in schools. - Proximity to the household for convenient maintenance and harvesting, composting of kitchen cuttings in the basket; - Ergonomic structure (raised, accessible). - Highly adaptable to local conditions that supports resilience to flood and drought conditions. - Highly productive—families produced vegetables even during the monsoon period. - As the keyhole garden normally does not need to be rebuilt every year it is a more efficient technique in the long-term than traditional methods such as pit and heap. Therefore, the reviewer did not suggest any major changes to the technique or project; rather to focus on specific issues that could help making the project more efficient and that could help broaden its impact. |

6.8 Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks of the Technology and ways of overcoming them

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the land user’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

|

No major weaknesses in the technology or design were expressed. However for some women it was difficult to access sufficient amounts of soil, which meant that they needed to walk long distances to bring soil to build the plinth. In coastal areas where saline intrusion in groundwater and soils is on the rise, growing and irrigating crops is difficult in the dry season. |

Some women received support from other family members or neighbours; identify a support network for families having challenges to access soil to build the plinths. Continue to look for for alternative irrigation sources and/or groundwater recharge innovations as well as soil conservation techniques to protect against salinity. Likewise, saline resistant vegetable varieties may be available. |

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

|

More careful planning of the location for the keyhole garden is needed. In Patharghata 11 women decided to relocate their garden within the first year. This suggests that the women appreciate the benefits of the garden, but having to break down and move the garden is a rather laborious activity. Not surprisingly, women who have less time to work in the homestead area, e.g. due to work or other out-of-home responsibilities, are not able to maintain their keyhole garden so well. |

Spend more time to assist the participants with identifying the most suitable locations to construct the garden for a keyhole garden in the homestead area at the start of the project. While maintaining a focus on women, involve the husband or other family members/ neighbours and ensure that they are also trained and ensure that the garden is clearly visible and can be accessed. |

7. References and links

7.1 Methods/ sources of information

- field visits, field surveys

50: The project evaluation took place from 4 June to 12 June 2013 with field visits in the two project areas, Kurigram and Patharghata. In total 5 Focus Group Discussions (FGD), with approximately 10 participants per FGD, were organized during this period. The core objective of the FGDs was to assess whether keyhole gardens have contributed to increases in vegetable production throughout the year and if this has lead to improved consumption practices. The additional aim of the FGDs was to learn directly from the participants about their nutritional needs and their ideas to further improve the keyhole garden project.

- interviews with land users

8: In addition to the FGDs the consultant carried out eight individual interviews with project

participants from the two regions. The individual interviews provided more detailed

information about production techniques and about the impact of the project at the

household level.

- compilation from reports and other existing documentation

Al-Amin S, 2012 and 2013, Tdh Bangladesh, Monthly Situation Reports for Garden Projects (unpublished)

Taylor S, 2013, Discussion paper for the Agrobiodiversity Conference, Dhaka, 28 January

2013, “Keyhole Gardens – great potential for improving homestead crop diversity and

mother & child nutrition”

Taylor S, 2012, Tdh Bangladesh, Project Report Homestead Garden for Greendots (unpublished)

Van Hout, 2013, Keyhole Gardens: Improved Access to Homestead Vegetables and Dietary Diversification, External Evaluation and Capitalization of the Keyhole Garden Project in Bangladesh (unpublished)

Varadi D, 2011, Tdh Bangladesh Field Visit Report for Greendots (unpublished)

When were the data compiled (in the field)?

02/08/2012

7.2 References to available publications

Title, author, year, ISBN:

"Keyhole Gardens: Improved Access to Homestead Vegetables and Dietary Diversification- External Evaluation and Capitalization of the Keyhole Garden Project in Bangladesh", Van Hout, R., 2013

Available from where? Costs?

Freely available: Terre des hommes Lausanne Asia Desk: info@tdh.ch

Title, author, year, ISBN:

“Keyhole Gardens – great potential for improving homestead crop diversity and mother & child nutrition”, Taylor S, 2013, Discussion paper for the Agrobiodiversity Conference, Dhaka, 28 January 2013

Available from where? Costs?

Freely available: Terre des hommes Lausanne Asia Desk: info@tdh.ch

Title, author, year, ISBN:

"Keyhole Gardens in Lesotho", FAO Nutrition and Consumer Protection Divis"ion (AGN), 2008 (with Send a Cow UK)

Available from where? Costs?

http://www.fao.org/ag/agn/nutrition/docs/FSNL%20Fact%20sheet_Keyhole%20gardens.pdf

7.3 Links to relevant online information

Title/ description:

Greendots - Terre des hommes technical partner for Keyhole Gardens in South Asia

URL:

www.greendots.ch

Title/ description:

Send a Cow UK: How to make an African style raised bed (YouTube, ex. Uganda)

URL:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ykCXfjzfaco

Title/ description:

Send a Cow UK - Keyhole Garden resources (Learning from Africa: How to make a Keyhole Garden)

URL:

http://www.sendacow.org.uk/lessonsfromafrica/resources/keyhole-gardens

Title/ description:

Fourthway's posters online: Smallholder organic agriculture (Uganda, including Keyhole gardens)

URL:

http://www.fourthway.co.uk/posters/

Title/ description:

Fourthway's posters online: Smallholder organic agriculture (Bangladesh, including Keyhole gardens)

URL:

http://www.fourthway.co.uk/bangladesh/index.html

Title/ description:

Terre des hommes: First Keyhole Garden in Asia (to resist storm surge/floods in Bangladesh)

URL:

https://vimeo.com/44043929

Links and modules

Expand all Collapse allLinks

Peer to Peer Pass-on Approach with Women [Bangladesh]

Terre des hommes and Greendots introduced the Peer to Peer pass-on system to enable women's groups in Bangladesh to spread the Keyhole Garden technique within their communities with the aim of enabling year-round homestead vegetable production despite the risk of flooding and tidal surge.

- Compiler: John Brogan

Modules

No modules