Joint village land use planning [Tanzania, United Republic of]

- Creation:

- Update:

- Compiler: Fiona Flintan

- Editor: –

- Reviewers: Donia Mühlematter, Simone Verzandvoort, Rima Mekdaschi Studer, Joana Eichenberger

approaches_3336 - Tanzania, United Republic of

View sections

Expand all Collapse all1. General information

1.2 Contact details of resource persons and institutions involved in the assessment and documentation of the Approach

Name of project which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

Sustainable Rangeland Management Project (ILC / ILRI)Name of project which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

Book project: Guidelines to Rangeland Management in Sub-Saharan Africa (Rangeland Management)Name of the institution(s) which facilitated the documentation/ evaluation of the Approach (if relevant)

ILRI International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) - Kenya1.3 Conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT

When were the data compiled (in the field)?

30/11/2016

The compiler and key resource person(s) accept the conditions regarding the use of data documented through WOCAT:

Yes

2. Description of the SLM Approach

2.1 Short description of the Approach

Joint village land use planning is a process facilitated by Tanzania's land policy and legislation. It supports the planning, protection and management of shared resources across village boundaries. It is an important tool towards land use planning and better rangeland management. This case study provides an example from a cluster of villages in Kiteto District, Tanzania.

2.2 Detailed description of the Approach

Detailed description of the Approach:

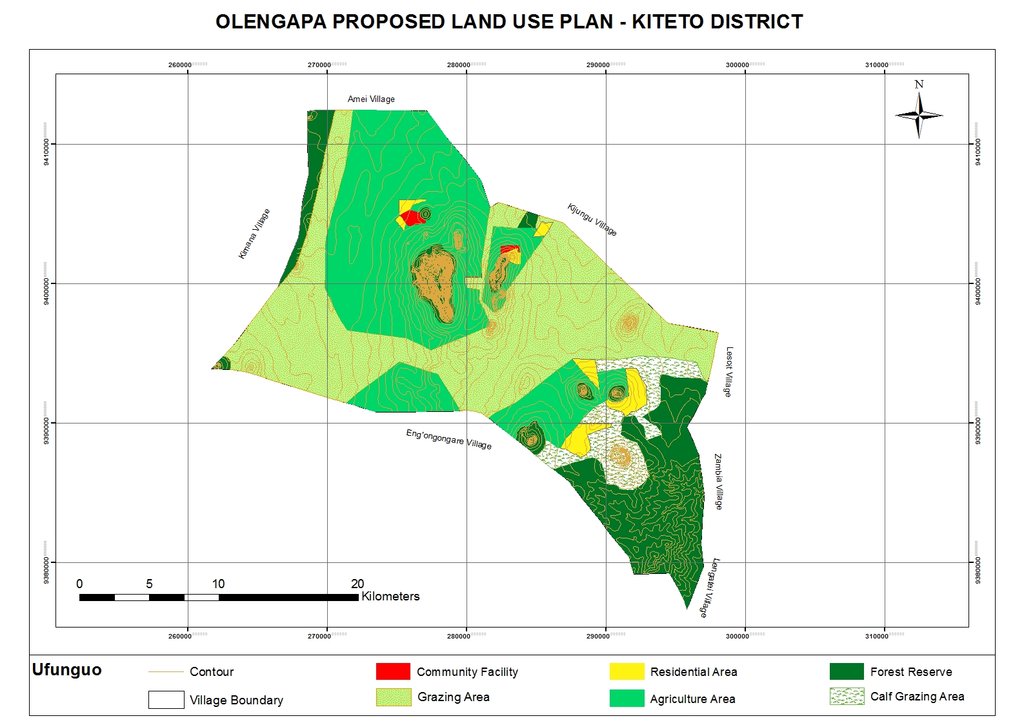

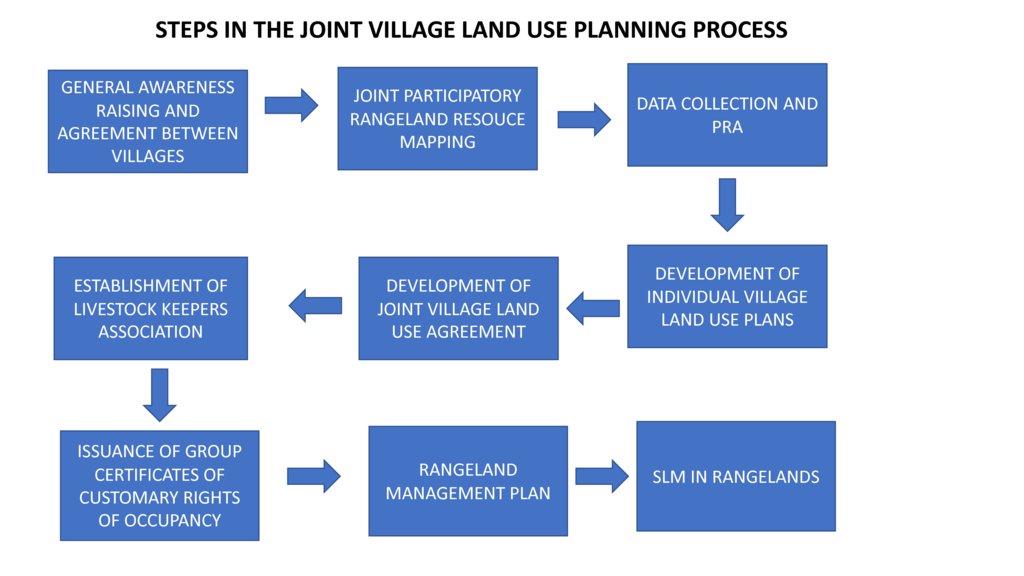

The Sustainable Rangeland Management Project (SRMP) is an initiative led by Tanzania’s Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries (MoLF), the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the National Land Use Planning Commission (NLUPC), with support from International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Irish Aid and the International Land Coalition (ILC). A key innovation of the project has been the development of joint village land use planning (JVLUP). The JVLUP process in Kiteto District, Manyara Region began in November 2013, and included the villages of Lerug, Ngapapa, and Orkitikiti. The three villages share boundaries and grazing resources, and in order to illustrate a single shared identity across the boundaries, the name OLENGAPA was chosen - incorporating part of each village’s name.

The total area of the three villages is (approx.) 59,000 hectares. The majority of inhabitants are Maasai pastoralists with some Ndorobo hunter-gatherers, and some farmers - most of whom are seasonal migrants. Mobility is central to the survival of the pastoralists and takes place across the three villages, as well as to locations in Kilindi, Gairo, and Bagamoyo Districts.

Average annual rainfall is between 800-1,000 mm per annum. There are no perennial rivers flowing through the OLENGAPA villages. The only permanent surface water source is Orkitikiti Dam, constructed in 1954.

In order to understand the different resources such as grazing areas, water points, cropping areas, livestock routes, and cultural places, SRMP supported participatory mapping. This assisted in developing a base map for the village land use planning process: it showed which resources were shared by the villages and where they were situated.

SRMP then helped village members to agree the individual village land use maps and plans - which zoned the village land into priority land uses - as well as the joint village land use map and plan, and the joint village land use agreement (JVLUA). These specified the grazing areas, water points, livestock routes and other shared resources. Reaching agreement was a protracted negotiation process between the villages, and within villages also - between different interest groups. It involved numerous community meetings and considerable investment of resources. Finally, each Village Assembly approved the JVLUA, which allocated approx. 20,700 ha of land for shared grazing –around 40% of the total village area. By-laws for management of the resources were developed and adopted.

Following approval of the JVLUA, the three OLENGAPA Village Councils established a Joint Grazing Land Committee made up of members from all three villages. This Committee is responsible for planning, management, enforcement of by-laws applicable to the OLENGAPA, and coordination of the implementation of both the OLENGAPA land use agreements and joint land use plan. In addition, a Livestock Keepers Association was established, including 53 founding members – but with most households from the three villages being associate members. A constitution was developed for the Association, which was officially registered on 11 September 2015.

In January 2016 the Ministry of Lands approved and registered the village land boundary maps and deed plans for the three villages. The District Council has issued the village land certificates, and the next step is for Village Councils to begin issuing Certificates of Customary Rights of Occupancy (CCROs). The shared grazing area will require three group CCROs to be issued to the Livestock Keepers Association – one from each village - for the part of the grazing area that falls under its jurisdiction. Signboards and beacons marking the shared grazing area are being put in place.

In November 2017 a fourth village joined OLENGAPA, expanding the shared grazing area to 30,000 ha. The villages are now working to develop a management plan to improve rangeland productivity.

2.3 Photos of the Approach

2.5 Country/ region/ locations where the Approach has been applied

Country:

Tanzania, United Republic of

Region/ State/ Province:

Manyara Region

Further specification of location:

Kiteto District

Comments:

Kiteto District, Manyara Region, Tanzania

Map

×2.6 Dates of initiation and termination of the Approach

Indicate year of initiation:

2010

Year of termination (if Approach is no longer applied):

2017

2.7 Type of Approach

- project/ programme based

2.8 Main aims/ objectives of the Approach

To secure shared grazing areas and other rangeland resources for livestock keepers, and to improve their management.

2.9 Conditions enabling or hindering implementation of the Technology/ Technologies applied under the Approach

social/ cultural/ religious norms and values

- enabling

History of collective tenure, management and sharing of rangeland resources as part of sustainable rangeland management practices.

- hindering

Marginalisation of pastoralists from decision-making processes at local and higher levels.

availability/ access to financial resources and services

- hindering

Village land use planning process is costly due to the requirement to include government experts in the process in order to gather required data and to authorise plans. Lack of government priority to village land use planning, so poor allocation of government funds to the process.

institutional setting

- enabling

Strong local government/community institutions for leading process at local albeit their capacity may require building.

collaboration/ coordination of actors

- hindering

Poor coordination of different actors supporting VLUP in the past due to previous weakness of National Land Use Planning Commission (NLUPC). However, this is now changing as NLUPC becomes stronger and takes up coordination role.

legal framework (land tenure, land and water use rights)

- enabling

Tanzania's legislation, if implemented well, provides an enabling environment for securing of community/village rights for both individuals and groups.

- hindering

Legislation allows village land to be transferred into public land if in the "public" or "national" interest - this facility confers insecurity on village land.

policies

- enabling

Tanzania possesses facilitating national land use policy for the joint village land use planning approach, together with guidelines.

- hindering

There are conflicting policies over land coming from different sectors including land generally, together with forests, wildlife and livestock. These cause confusion at the local level. Depending on power of actors one set of policies may be stronger than another - wildlife-related policy for example can have a lot of power because there are many strong and influential tourism and conservation bodies lobbying for stronger protection of land, with potentially negative impacts for communities who want to use that land for other purposes.

land governance (decision-making, implementation and enforcement)

- enabling

Decision-making has been decentralised to the lowest levels, giving local communities considerable power to decide on the uses of their village land.

- hindering

The process of village land use planning is costly due to the requirement for having local government experts involved, and the need to follow often complex procedures and steps. Many communities and even local government do not have adequate technical skills and knowledge to complete the long process, as well as not having adequate funds. This has held up the VLUP applications. Further few VLUPs move from their production stage to implementation stage including enforcement of bylaws and, for example, land management.

knowledge about SLM, access to technical support

- enabling

Good local knowledge of rangeland management based on historical practice. Communities understand need for better rangeland management.

- hindering

Lack of investment in rangeland management and the provision of technical support e.g. through government extension services. Lack of technical knowledge in rangeland rehabilitation and improving rangeland productivity at scale.

markets (to purchase inputs, sell products) and prices

- hindering

Lack of local markets and coordinated operations for livestock production.

workload, availability of manpower

- enabling

Well-structured local community bodies ready to provide manpower. Local government experts in place to support VLUP process.

- hindering

Lack of knowledge, skills and capacity amongst local communities and government experts to complete JVLUP adequately, including such as resolving conflicts between different land users.

3. Participation and roles of stakeholders involved

3.1 Stakeholders involved in the Approach and their roles

- local land users/ local communities

Village members (Assembly) of three villages - Orikitiki, Lerug and Ngapapa.

All village members as the Village Assembly have an opportunity to contribute to the land use planning process and to approve it.

- community-based organizations

Village Council, Village Land Use Management Committee (VLUMC), Rangeland Management Committee, Livestock Keepers Association.

Village government coordinated the planning process at local level. VLUMC develops plan. Village Council approves plans and issues CCROs. Rangeland Management Committee oversees development in rangelands. Livestock Keepers Association established made-up of all members of the villages that have livestock (nearly all village members) - they will be issued with CCROs as "owners" of the grazing land.

- SLM specialists/ agricultural advisers

Land use planning consultants

Provision of advice to the project team, local government and villagers on the JVLUP approach.

- researchers

International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Identification of good practice in village land use planning in Tanzania and ways to adapt and incorporate good practice into joint village land use planning to improve the approach. Research on role of and impact on pastoral women. Undertaking of baseline studies.

- NGO

KINNAPA Development Association (supported originally by CARE and Tanzania Natural Resource Forum).

KINNAPA is the local CSO partner working as part of the project to implement the JVLUP with local communities

- local government

District Council including the PLUM (participatory land use management planning experts)

The District Council provides local government oversight of the planning process and approves the plan before submitting to national government body. The PLUM technically supports the development of the JVLUP working with the village government(s) and village committees.

- national government (planners, decision-makers)

Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries, National Land Use Planning Commission (NLUPC), Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development,

Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries leading the planning process with a sectoral interest in protecting rangelands. NLUPC provides technical oversight and guidance. Ministry of Lands is the national body that approves the final plan.

- international organization

International Land Coalition (ILC)

ILC is the grant recipient for the funds from the donors. The project is implemented through ILC members such as ILRI. ILC coordinates its members work in Tanzania on land issues including the JVLUP through a national engagement strategy (NES). ILC also provides technical support to the process through its global/Africa programme - the ILC Rangelands Initiative. The ILC Rangelands Initiative is a platform for learning, sharing, influencing, and connecting on rangeland issues with the objective of making rangelands more secure.

- Donors

IFAD and Irish Aid

Provide funds for the project. IFAD also provides technical support on land tenure issues.

If several stakeholders were involved, indicate lead agency:

The lead agency is the International Land Coalition (ILC) working through its members including ILRI. In country, the main implementer is the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries

3.2 Involvement of local land users/ local communities in the different phases of the Approach

| Involvement of local land users/ local communities | Specify who was involved and describe activities | |

|---|---|---|

| initiation/ motivation | external support | The project supported communities to initiate the first steps taken to reach agreement on the need for planning and how this would be done. |

| planning | interactive | Communities were centrally involved in the planning of the VLUP process, with support from local NGO and government. |

| implementation | interactive | Village government and community in general is responsible for the implementation of the planning process, with the support of local government. |

| monitoring/ evaluation | external support | The community is responsible for monitoring and evaluation, but lack skills and capacity in this regard requiring external support. |

| Research | external support | Research on information required for planning processes collected and generated by communities with the assistance of technical support from local NGO, local government and researchers. |

3.3 Flow chart (if available)

3.4 Decision-making on the selection of SLM Technology/ Technologies

Specify who decided on the selection of the Technology/ Technologies to be implemented:

- all relevant actors, as part of a participatory approach

Explain:

The policy and legislation lays down the steps to be followed for the VLUP/JVLUP process. However there is room to adapt these processes to local context - and here all stakeholders were involved to develop the process of JVLUP through its first piloting. This included communities, local and national government, local NGOs, researchers and development organisations.

Specify on what basis decisions were made:

- evaluation of well-documented SLM knowledge (evidence-based decision-making)

4. Technical support, capacity building, and knowledge management

4.1 Capacity building/ training

Was training provided to land users/ other stakeholders?

Yes

Specify who was trained:

- land users

- field staff/ advisers

- government staff

Form of training:

- on-the-job

- public meetings

- courses

Subjects covered:

Land users were trained in land related and other relevant laws and the JVLUP process. Field staff/advisers were trained in land laws, the JVLUP process, gender, and conflict resolution. Local government were trained in the JVLUP process, gender and conflict resolution.

4.2 Advisory service

Do land users have access to an advisory service?

No

4.3 Institution strengthening (organizational development)

Have institutions been established or strengthened through the Approach?

- yes, greatly

Specify the level(s) at which institutions have been strengthened or established:

- local

- national

Describe institution, roles and responsibilities, members, etc.

Local government bodies including Village Council, VLUMC (village land use management committee) and Livestock Keepers Association have all had capacity strengthened, but more is required (particularly for the latter). Capacity of the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries and the National Land Use Planning Commission to implement JVLUP has been built.

Specify type of support:

- financial

- capacity building/ training

- equipment

- data collected and database set up

4.4 Monitoring and evaluation

Is monitoring and evaluation part of the Approach?

Yes

Comments:

M&E has not been strong in previous phases, but now is central with baselines being carried out in all new clusters of villages where the project will work so that impact can be fully assessed.

If yes, is this documentation intended to be used for monitoring and evaluation?

No

4.5 Research

Was research part of the Approach?

Yes

Specify topics:

- sociology

- economics / marketing

- ecology

Give further details and indicate who did the research:

Research was carried out to identify good practice (in terms of social, economic and environmental impacts) from which the JVLUP process was developed. In future phases the full impacts of this JVLUP in terms of social, economic and ecological impact are being researched.

5. Financing and external material support

5.1 Annual budget for the SLM component of the Approach

If precise annual budget is not known, indicate range:

- 10,000-100,000

Comments (e.g. main sources of funding/ major donors):

IFAD, Irish Aid,

5.2 Financial/ material support provided to land users

Did land users receive financial/ material support for implementing the Technology/ Technologies?

No

5.3 Subsidies for specific inputs (including labour)

- none

If labour by land users was a substantial input, was it:

- voluntary

Comments:

Labour was voluntary with meal provided and/or travel costs covered.

5.4 Credit

Was credit provided under the Approach for SLM activities?

No

5.5 Other incentives or instruments

Were other incentives or instruments used to promote implementation of SLM Technologies?

Yes

If yes, specify:

Tanzanian policy and legislation states that all village should have a VLUP, therefore this was an incentive for stakeholders to invest in the process. In addition conflicts over land use are increasingly a problem in Tanzania - so the resolution of these was also an important incentive.

6. Impact analysis and concluding statements

6.1 Impacts of the Approach

Did the Approach empower local land users, improve stakeholder participation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Local village communities now feel strongly empowered in protecting and managing their land. The process has brought different stakeholders together and strengthened commitment to make the process work.

Did the Approach enable evidence-based decision-making?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The piloting of the JVLUP showed what is possible and the positive impacts realised (albeit they could have been better documented). On these results the process is being scaled-up.

Did the Approach help land users to implement and maintain SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The planning process has laid the foundations for improved rangeland management - what is now required is investment in that management.

Did the Approach improve coordination and cost-effective implementation of SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Did the Approach mobilize/ improve access to financial resources for SLM implementation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of land users to implement SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Land users have greater knowledge of the potential and need for rangeland management based on a better understanding of their land and resources gained through the JVLUP process, but they still need skills and resources to put this knowledge into action.

Did the Approach improve knowledge and capacities of other stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

National and local government have seen the potential of the JVLUP to resolve conflicts over land use, and their capacities to implement the JVLUP in this regard has been improved.

Did the Approach build/ strengthen institutions, collaboration between stakeholders?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

The approach is helping build relations between the Ministry Livestock and Fisheries and the NLUPC together with NGO(s) at national level, as well as between different stakeholders involved in JVLUP at local levels.

Did the Approach mitigate conflicts?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Through the process of JVLUP the roots of land use conflicts come to the surface and must be resolved before agreement is reached. This may cause tensions and even conflict along the way - but the outcome should be positive.

Did the Approach empower socially and economically disadvantaged groups?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Pastoralists are often left out of village land use planning processes. This approach when implemented well gives greater opportunity for them to be involved. However this is still a challenge.

Did the Approach improve gender equality and empower women and girls?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Women can be left out of village land use planning processes. This approach when implemented well gives greater opportunity for them to be involved. However this is still a challenge.

Did the Approach encourage young people/ the next generation of land users to engage in SLM?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Youth can be left out of village land use planning processes. This approach when implemented well gives greater opportunity for them to be involved. However this is still a challenge.

Did the Approach improve issues of land tenure/ user rights that hindered implementation of SLM Technologies?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

By following the JVLUP process village land has been certified and secured, as well as the rights of access and use of livestock keepers to the grazing land.

Did the Approach lead to improved food security/ improved nutrition?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

This has not been specifically monitored but it assumed by having stronger security to land and resources, food security and nutrition will be improved.

Did the Approach improve access to markets?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

This has not been specifically monitored but it assumed by having stronger security to land and resources, access to markets will be improved.

Did the Approach lead to improved access to water and sanitation?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

In terms of water for livestock the JVLUP process has secured rights for the three villages to shared water resources.

Did the Approach lead to more sustainable use/ sources of energy?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

Did the Approach improve the capacity of the land users to adapt to climate changes/ extremes and mitigate climate related disasters?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

By having stronger security to land and resources local land users are better placed to adapt to climate change etc.

Did the Approach lead to employment, income opportunities?

- No

- Yes, little

- Yes, moderately

- Yes, greatly

This has not been specifically monitored but it assumed by having stronger security to land and resources, income opportunities will be improved.

6.2 Main motivation of land users to implement SLM

- increased production

By protecting grazing areas, there will be more secure access to resources required for livestock production.

- reduced land degradation

By protecting grazing areas and improvement of rangeland management practices land degradation will be reduced.

- reduced risk of disasters

With more secure access to land and resources, local land users are better placed to manage their resources in order to reduce risks to disasters.

- rules and regulations (fines)/ enforcement

By gaining protection from village certification, village land use planning and local bylaws developed as part of this, local land users are better placed to enforce rules and regulations relating to land use and to prevent encroachment/trespassing by outsiders.

- prestige, social pressure/ social cohesion

The JVLUP process improved the social cohesion and group identify of the three villages - expressed in the name OLENGAPA (made up of the three village names). There is a strong livestock keepers association now made up of livestock keepers from all three villages who are working more closely together.

- conflict mitigation

The JVLUP helped to resolve land use conflicts by opening up space to discuss root causes, find solutions and come to agreement between land users.

6.3 Sustainability of Approach activities

Can the land users sustain what has been implemented through the Approach (without external support)?

- uncertain

If no or uncertain, specify and comment:

The community requires support from local government to protect their village lands including grazing lands from outsiders wanting to settle on the land - this is a constant problem to be addressed (despite the securing of village boundaries etc.). The community also needs capacity building and resources to improve the productivity of the land including the grazing areas. If they get these supports then they can sustain what has been implemented.

6.4 Strengths/ advantages of the Approach

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the land user’s view |

|---|

| Improved the security of access and use to village land including grazing. |

| Brought attention to the challenges faced by land users in the area in protecting and using their village land, and the need for more investment and support for this. |

| Pastoralists are now more central to decision-making processes than they were before. |

| Strengths/ advantages/ opportunities in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view |

|---|

| Collaboration of different stakeholders in implementing the approach has supported a new way of working. |

| Capacity of different stakeholders has been built along the way through joint problem-solving and learning-by-doing. |

| The approach - with adaptation - has application in other contexts/countries and shows that even if a rangeland is split by administrative boundaries there is opportunity to work across those village boundaries in order to maintain the functionality of the rangeland and land use systems such as pastoralism that depend upon this. |

6.5 Weaknesses/ disadvantages of the Approach and ways of overcoming them

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the land user’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

| Despite village land being theoretically protected, in practice it can still be encroached upon. | Greater support provided from government to enforce protection of land. |

| Time-consuming process which became more expensive than anticipated resulting in some gaps in funding. | Process needs to be refined through practice, and adequate funds allocated from beginning. |

| Weaknesses/ disadvantages/ risks in the compiler’s or other key resource person’s view | How can they be overcome? |

|---|---|

| The selection of villages for JVLUP needs more care to ensure that enabling conditions for JVLUP exist. | In future selection of villages for JVLUP a set of criteria should be used that enable more enabling conditions to exist. |

| Information has not been methodologically collected on social, environmental and economic impacts of the approach. | In future the impacts of the approach need to be fully monitored and evaluated. |

| The VLUP is an expensive process to follow. | National government needs to identify ways to reduce the cost of the VLUP so that more villages can undertake it. Government needs to allocate more funds to VLUP. The VLUP is an expensive process to follow. |

| Need for an enabling environment. | The policy and legislation in Tanzania enables this process - it is not the case in the majority of other African countries. |

7. References and links

7.1 Methods/ sources of information

- compilation from reports and other existing documentation

The compiler has been involved in the project/process since its inception and had access to all reports and existing documentation.

7.3 Links to relevant information which is available online

Title/ description:

Kalenzi, D. 2016. Improving the implementation of land policy and legislation in pastoral areas of Tanzania: Experiences of joint village land use agreements and planning. Rangelands 7. Rome, Italy: International Land Coalition.

URL:

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/79796

Title/ description:

Daley, E., Kisambu, N. and Flintan, F. 2017. Rangelands: Securing pastoral women’s land rights in Tanzania. Rangelands Research Report 1. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

URL:

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/89483

Title/ description:

International Livestock Research Institute. 2017. Sustainable Rangeland Management Project, Tanzania. ILRI Project Brochure. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

URL:

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/80673

Title/ description:

International Land Coalition. 2014. Participatory rangeland resource mapping in Tanzania: A field manual to support planning and management in rangelands including in village land use planning. Rome: International Land Coalition

URL:

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/51348

Title/ description:

Flintan, F., Mashingo, M., Said, M. and Kifugo, S.C. 2014. Developing a national map of livestock routes in Tanzania in order to value service and protect them. Poster prepared for the ILRI@40 Workshop, Addis Ababa, 7 November 2014. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

URL:

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/64964

Title/ description:

Village land use planning in rangelands in Tanzania, F. Flintan 2012

URL:

http://www.landcoalition.org/en/regions/africa/resources/no-3-village-land-use-planning-rangelands-tanzania

Title/ description:

Protecting shared grazing through joint village land use planning

URL:

http://www.landcoalition.org/en/regions/africa/resources/protecting-shared-grazing-through-joint-village-land-use-planning

Links and modules

Expand all Collapse allLinks

No links

Modules

No modules